The Prisoner’s Dilemma is one of the most well-known models in game theory, demonstrating how personal interests can conflict with the common good. In the classic example of the dilemma, two suspects of a crime are detained separately and offered the following conditions: if one confesses while the other remains silent, the one who speaks will receive minimal punishment, while the silent one will receive the maximum. If both cooperate with the investigation, they both receive moderate sentences. However, if both remain silent, the punishment will be minimal for each.

This model shows how difficult decision-making can be, especially when an individual does not know how the other will act. The main challenge of the dilemma lies in the conflict between short-term gain and long-term interest. This makes the Prisoner’s Dilemma a universal model for analyzing social, economic, and even moral situations.

In the modern world, moral choice is an integral part of every person’s life. In the context of globalization, social interaction, and high levels of competition, we face situations daily where we must choose between personal benefit and ethical principles. The Prisoner’s Dilemma, as a model, is particularly relevant in the context of modern realities:

- In business, where companies can choose between cooperation or competition.

- In interpersonal relationships, where honesty can become the basis of trust or a source of conflict.

- In political and environmental decisions, where it is necessary to balance national interests with global goals.

Moral dilemmas are becoming increasingly complex due to society’s interdependence. People often hesitate between what is “right” and what is “profitable,” and resolving these dilemmas affects not only individuals but also entire groups, communities, or even countries.

Honesty is usually considered the morally correct choice. It is associated with values such as trust, reliability, and mutual respect. However, honesty does not always bring immediate benefits, especially in situations like the Prisoner’s Dilemma. For example:

- In the short term, betrayal may seem like a more rational strategy because it allows one to gain the maximum personal benefit.

- In the long term, however, a lack of honesty can lead to a loss of trust, making future cooperation impossible.

This issue is key not only within game theory but also in real life. Is it always beneficial to be honest? Are there situations where deviating from moral principles is justified? The answers to these questions lie in a deep analysis of the Prisoner’s Dilemma and its application to life circumstances.

What is the Prisoner’s Dilemma?

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is one of the most famous examples in game theory, illustrating the complexity of choosing between personal interests and the common good. It shows how individual decisions, made under uncertainty about the actions of the other party, can lead to an outcome that is less beneficial for all participants. This concept, developed in the mid-20th century, is used to analyze conflicts, cooperation, and strategic thinking in various areas of life.

In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the main intrigue lies in the fact that the optimal strategy for each participant individually does not always provide the best result for both. In real life, the Prisoner’s Dilemma is reflected in many spheres—from personal relationships to global political issues. Its universality and depth make this concept essential for understanding not only individual but also collective behavior.

Classic Example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma

Let us imagine two suspects of a crime who are interrogated separately. The police do not have enough evidence to prove their guilt without one of them confessing. Therefore, they are offered the following conditions:

- If one confesses while the other remains silent, the traitor will go free, while the silent one will be sentenced to 10 years in prison.

- If both confess, each will receive 5 years.

- If both remain silent, they will each receive 1 year for a minor offense.

Each suspect faces a choice: to confess or to remain silent. The problem is that neither knows how the other will act. The rational strategy seems to be confessing, as it reduces the risk of maximum punishment. However, if both choose to confess, their joint outcome will be worse than if both had remained silent.

This example demonstrates the fundamental paradox of the Prisoner’s Dilemma: individual gain does not always align with the common interest.

Applications of This Model in Different Areas of Life

- Personal relationships: In relationships, the Prisoner’s Dilemma often manifests in situations where trust and honesty are key. For example, spouses may hide the truth out of fear of conflict, which in the long run leads to a loss of trust. Another example is friendship, where one friend might break an agreement, hoping the other does not do the same.

- Business: In the business environment, the Prisoner’s Dilemma often arises in competitive strategies. For example, two companies can either cooperate to maintain prices in the market or lower them to attract customers. If both lower prices, their profits will decrease, although cooperation could bring greater benefits to both.

- Politics: In international politics, the Prisoner’s Dilemma is reflected in issues of disarmament, climate agreements, or sanctions. For example, countries may agree to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but the fear that others will break the agreement prompts them not to fulfill their promises. As a result, the global problem remains unresolved, and trust between countries decreases.

The Concept of Rational Choice in the Context of the Dilemma

Rational choice is a decision that maximizes the benefit for a specific individual in a specific situation. In the context of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the rational choice appears to be confession, as it guarantees a better outcome for the individual, regardless of the actions of the other participant.

However, the paradox is that the rational choice for each individually leads to a suboptimal result for both. This situation demonstrates the limitations of the rational approach, especially in conditions of interdependence. In real life, rational choice is often adjusted through trust, cooperation, or moral principles, allowing for a more advantageous collective result.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma thus raises key questions: is rationality always optimal? And how can morality influence strategic thinking?

Moral Choice in the Prisoner’s Dilemma

The prisoner’s dilemma is not only a mathematical model but also a metaphor for the moral choices individuals face in everyday life. This situation intertwines two fundamental aspects of human behavior: the pursuit of personal benefit and the necessity to adhere to ethical principles. When confronted with the dilemma, people often need to choose between self-interest and the welfare of others, leading to profound internal conflicts.

The moral choice within the context of the prisoner’s dilemma highlights the challenge of balancing honesty, trust, and the fear of being deceived. In real life, this issue becomes even more complex, as the consequences of decisions are often unpredictable. Thus, the prisoner’s dilemma serves as a valuable tool for analyzing moral behavior in situations where rational gain may conflict with ethical norms.

To delve deeper into this phenomenon, we should examine specific aspects of moral choice, including the contradictions between benefit and ethics, real-life examples, and the analysis of potential behavioral strategies.

Contradictions Between Rational Benefit and Ethical Principles

One of the primary issues in the prisoner’s dilemma is that rational benefit for an individual often conflicts with general ethical norms. For example, choosing betrayal may provide immediate personal gain but simultaneously violates the moral principle of honesty.

This contradiction demonstrates the complexity of choice, as individuals must consider not only the material consequences of their decisions but also their impact on relationships, trust, and social norms. In many cases, acting rationally for self-gain leads to the erosion of trust, which is the foundation of any collaboration.

Ethical choices in the prisoner’s dilemma depend on the context: whether the situation is one-time or recurring. In recurring scenarios, people are more inclined to act morally, as the consequences of breaching trust can be long-term and significant.

Real-Life Examples Where Choices Between Honesty and Personal Gain Arise

- Personal Relationships. In everyday life, the prisoner’s dilemma manifests in relationships between individuals. For instance, a situation may arise in a marriage where one partner has the opportunity to hide important information for their own benefit, hoping the other will never find out. While hiding the truth may seem like a rational strategy, it can lead to a loss of trust and the breakdown of the relationship.

- Business Environment. In business, honesty and gain often become opposing poles. For example, a company may decide to conceal flaws in its product to secure immediate profits. However, if the truth comes out, reputational damage may far outweigh the short-term benefits.

- Politics. In political relations, the prisoner’s dilemma appears in decisions about cooperation or confrontation. For instance, countries may agree to disarmament, but fear of betrayal by the other side often leads to breaches of agreements. This creates situations where moral choices (trust and honesty) are overshadowed by pragmatic approaches.

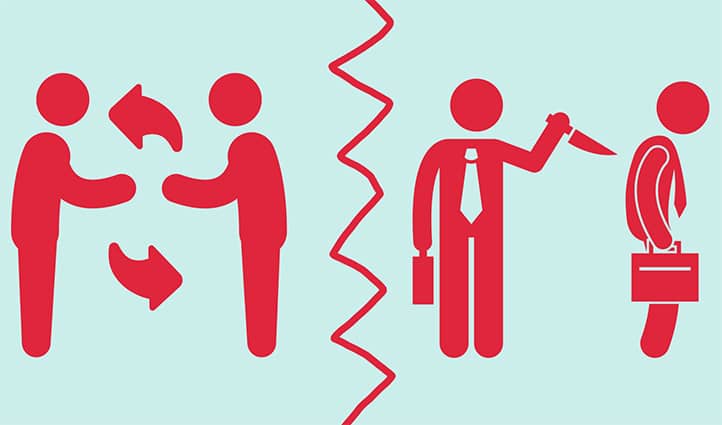

Analysis of Behavioral Strategies: Cooperation vs. Betrayal

- Cooperation Strategy. Cooperation is based on mutual trust and moral principles. It is advantageous in the long term, especially in recurring situations, where trust between participants leads to better outcomes. For instance, in the classic example of the prisoner’s dilemma, both silent suspects receive minimal punishment, demonstrating the benefits of cooperation.

- Confession Strategy. Confession often appears to be a rational strategy, as it may provide maximum benefit for one party. However, this strategy carries risks: if both parties confess, the overall outcome will be significantly worse than in the case of cooperation.

- Outcome Analysis. The prisoner’s dilemma shows that the choice of strategy depends on numerous factors: the level of trust, the value of ethical principles for the participants, and their willingness to cooperate. In real life, the cooperation strategy proves more stable, as it fosters the preservation of relationships and long-term benefits.

Thus, moral choice in the prisoner’s dilemma depends not only on the pursuit of gain but also on the ability to adhere to ethical norms even in challenging situations. This underscores the importance of balancing rationality and morality when making decisions.

Honesty as a Strategy

Honesty is one of the fundamental ethical values that builds trust between individuals and promotes harmonious relationships in society. In the context of the prisoner’s dilemma, honesty, like any other strategy, has its advantages and risks, and its effectiveness depends on specific circumstances.

In real life, honesty is not always an obvious choice. People often face situations where openness and sincerity can lead to vulnerability or the loss of immediate benefits. Nevertheless, in many cases, honesty helps maintain reputation, uphold trusting relationships, and secure societal support. To better understand honesty as a strategy, it is worth examining its advantages, risks, and cases where it does not lead to success.

Advantages of Honesty

Honesty offers several significant advantages that make it an important strategy in interpersonal, social, and professional settings:

- Building Trust. Trust is a key element of any interaction. Honest individuals instill a sense of security in others, fostering open and constructive relationships. For example, in business, honest partners more easily reach agreements and reduce the risk of conflicts.

- Long-Term Benefits. Although honesty may not yield immediate results, it ensures stable long-term benefits. Honest individuals often gain loyalty from others, which becomes a foundation for sustainable relationships. In recurring situations, the honesty strategy proves more advantageous as it preserves the basis for future cooperation.

- Social Support. Honest people generally receive greater support from those around them, as their actions align with moral norms. Such individuals inspire sympathy and respect, which becomes a valuable resource in challenging situations.

Risks of Honesty

Despite its advantages, honesty carries certain risks that make this strategy challenging in some circumstances:

- Vulnerability to Betrayal. Honesty often leaves an individual vulnerable, especially when the other party acts dishonestly. This creates a serious moral dilemma, as acting openly becomes risky.

- Loss of Immediate Gain. Sometimes, honesty requires sacrifices, such as foregoing short-term benefits. For instance, during negotiations, openly admitting one’s weaknesses may give an advantage to competitors, even though it creates a better atmosphere for future cooperation.

- Misunderstandings. Honesty can sometimes lead to conflicts if the truth does not meet the other party’s expectations. For example, in interpersonal relationships, candidness about difficult issues may cause disappointment or even aggression.

Examples Where Honesty Does Not Lead to Success

While honesty has numerous advantages, there are cases where it is not an effective strategy:

- Business Situations. In certain fields, competition is so intense that openness can be used against those who choose honesty. For example, a company openly admitting problems with its product risks losing customers, even if this transparency may improve its reputation in the long run.

- Political Conflicts. In politics, honesty often becomes an obstacle to success. For instance, a political leader who openly admits their mistakes may lose the trust of voters due to high societal expectations, where reputation sometimes outweighs truth.

- Personal Relationships. In some situations, honesty can harm relationships. For example, excessive openness about a partner’s past may provoke jealousy or a loss of trust, even if the intention was sincere.

Honesty as a strategy is a complex choice that requires consideration of many factors. Its effectiveness depends on the context, the values of the individual, and their willingness to take risks. Despite the challenges, honesty remains an important principle that fosters trust and harmony in society.

Research and Experiments

The study of the Prisoner’s Dilemma has become a cornerstone of game theory, as it enables the analysis of strategic human behavior in various situations. Researchers have actively used this model to conduct experiments that reveal the nature of human cooperation, mutual trust, and the influence of ethical principles on decision-making. Particular attention has been given to repeated games, where participants repeatedly face the choice between cooperation and betrayal.

Experiments with the Prisoner’s Dilemma have also highlighted the importance of honesty in long-term interactions. Honesty not only forms the foundation for stable cooperation but also influences partner behavior, fostering trust. These studies are crucial for understanding how moral principles affect real-world social and economic processes.

Results of Experiments in the Context of the Prisoner’s Dilemma

One of the most well-known experiments involving the Prisoner’s Dilemma was conducted by Anatol Rapoport during a game theory tournament in the 1980s. His “Tit-for-Tat” strategy became one of the most successful in repeated games. This strategy involved:

- Initial cooperation.

- Responding to the partner with the same action they demonstrated in the previous round (cooperation for cooperation, betrayal for betrayal).

The experiment’s results showed that cooperation is the most beneficial in the long term, even if betrayal may offer immediate benefits. Repeated games allowed participants to consider their partners’ past actions, which helped build trust and avoid conflicts.

Other studies demonstrated that participants who adhered to honesty in their decisions built a positive reputation, even among those who initially chose betrayal. Random shifts to betrayal often destroyed trust, while consistent honesty encouraged cooperation.

How Does Honesty Affect Partner Behavior in Long-Term Interactions?

Honesty plays a crucial role in long-term relationships as it creates an environment of predictability and mutual support. Researchers have observed that partners who adhere to honesty inspire their colleagues to reciprocate in kind.

- Building trust. In long-term interactions, trust becomes the foundation for cooperation. For example, experiments have shown that people who honestly shared information or resources received greater support from partners in subsequent rounds. Even if others initially chose betrayal, consistent honesty shifted their behavior toward cooperation.

- Improving communication. Honesty allows partners to exchange information without fear of being deceived. This is especially important in business or politics, where transparency forms the basis for decision-making. For instance, in long-term negotiations, honesty helps reduce tension and fosters an atmosphere of collaboration.

- Reputational effect. People who remain honest even in challenging situations gain a reputation as reliable partners. This creates an advantage in the long term, as those around them begin to value such behavior.

Studies and experiments in the context of the Prisoner’s Dilemma vividly demonstrate that honesty profoundly impacts the dynamics of cooperation. Although short-term benefits sometimes encourage betrayal, consistent honesty helps build stable and mutually beneficial relationships in any sphere of life.

Morality Versus Rationality

The Prisoner’s Dilemma vividly illustrates the conflict between moral principles and rational reasoning. People often find themselves in situations where they must choose between what is ethically right and what is immediately advantageous. This balance is not always obvious and often depends on external circumstances, personal beliefs, and social or cultural factors.

Rationality is often viewed as a pragmatic approach to maximizing benefits. Morality, in contrast, is based on ideals of justice, honesty, and respect for others. The choice between them is not just a personal dilemma but a profound philosophical issue that influences various aspects of life, from interpersonal relationships to political decisions.

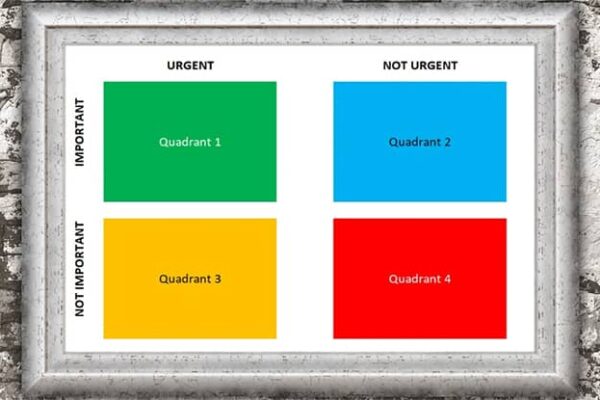

Balancing Ethical Principles and Pragmatic Approaches

The balance between morality and rationality depends on many factors, with context playing a key role.

- Personal beliefs. People deeply rooted in their ethical principles are often willing to sacrifice short-term gains to uphold moral norms. For example, in the context of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, they might choose cooperation even while understanding that their partner might betray them.

- Rational benefits. Rationality dictates maximizing one’s advantages. In the classic example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the rational choice is betrayal, as it minimizes personal risk regardless of the partner’s behavior. However, in repeated situations, the balance shifts toward cooperation since long-term benefits become more significant than immediate ones.

- Context of the situation. In some cases, circumstances influence the choice: for instance, when the decision concerns not only personal interests but also the interests of a group to which one belongs. The balance between morality and rationality becomes particularly complex in such conditions.

Can Honesty Always Be Reconciled with Rational Choice?

The question of whether honesty and rationality can always be reconciled sparks much debate, as these two categories do not always harmonize.

- Honesty as a long-term strategy. In many cases, honesty is rational in the long run. For example, in business, building a reputation as an honest partner often yields greater benefits than deceit, even if the latter might provide an immediate advantage.

- The impossibility of reconciliation. There are situations where honesty cannot be justified rationally. For instance, when an honest response or action could harm an individual or group. In such cases, a person may face a difficult moral choice.

- The case of the Prisoner’s Dilemma. In the classic example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, honesty (i.e., mutual cooperation or silence) may seem unreasonable if one party chooses betrayal (confession). However, in repeated games, where decisions are based on prior experiences, honesty often proves to be an effective strategy as it builds trust and stability in relationships.

The Influence of Social and Cultural Norms on Strategy Choice

Social and cultural factors significantly affect how people resolve the conflict between morality and rationality.

- Culture of cooperation. In cultures where cooperation is highly valued, people are more likely to choose ethical strategies. For example, in Scandinavian countries known for their social principles, people tend to choose honesty even in challenging situations.

- Culture of individualism. In societies dominated by individualism, people are more likely to choose rational strategies aimed at maximizing personal gain. This is evident in many Western countries, where competition is considered the driving force of success.

- Social pressure. In some cases, the choice of strategy depends on group expectations. For example, in business, social norms may dictate that deceit is acceptable if it brings profit. However, in such cases, the risk of losing reputation is also high.

Morality and rationality often come into conflict, and the choice between them depends on personal beliefs, context, and the influence of external factors. In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, this tension becomes a vivid example of how difficult it can be to balance benefit and ethical principles.

Conclusion

Honesty is a multifaceted concept that serves both as an ethical principle and a strategic tool. On the one hand, it builds trust, ensures long-term benefits in relationships, and strengthens social bonds. On the other hand, honesty is often associated with risks: it can make a person vulnerable, create the danger of losing immediate benefits, or even lead to unfavorable outcomes in complex situations where others choose deception or betrayal.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma, as a model of game theory, is a universal tool for analyzing such situations. It demonstrates how the balance between cooperation and selfish gain affects outcomes in various spheres of life, from business and politics to personal relationships. The practical application of this concept reveals that rational behavior does not always lead to optimal results, especially in the long run. Repeated interactions show that choosing cooperation and honesty usually brings greater benefits by fostering stability and mutual trust.

However, in real life, situations are not always as schematic as in game theory. People face much more complex circumstances where moral principles conflict with pragmatism. Here, social and cultural factors come to the forefront, shaping the framework for decision-making. For example, in societies with a strong orientation toward cooperation, honesty may be considered a core principle, whereas in individualistic cultures, decisions are often made based on personal gain.

To make the right choice in complex moral situations, it is important to consider several aspects:

- First, assess whether it is possible to find a balance between ethicality and pragmatism that ensures an optimal outcome.

- Second, consider the long-term consequences of your actions, as short-term benefits may result in significant losses in the future.

- Third, take into account the social context and possible reactions from other participants.

Thus, the Prisoner’s Dilemma is not just a theoretical model but a practical tool for understanding moral choices in everyday life. It reminds us of the importance of a balanced approach that considers both ethical principles and rational considerations. Understanding these mechanisms helps make decisions that not only align with personal interests but also contribute to building a harmonious and responsible society.

Do You Always Choose Honesty in Your Own Life?

Everyone has encountered situations where honesty could harm them or put them in an uncomfortable position. For example, do you always tell the truth, even when it might cause conflict or hurt someone’s feelings? Should you always be honest with your boss, even if it could affect your career? These questions have no clear answers, but they allow for deeper reflection on how much we are guided by moral principles in daily life.

Think about whether you’ve ever chosen dishonesty for a quick result but later regretted it in the long term. Have you had situations where you chose honesty despite the risks and felt proud of your decision? Answering these questions can shed light on your own value system.

How Would You Act in the Prisoner’s Dilemma?

Imagine you are faced with a choice: act in your self-interest or cooperate, risking the loss of benefits. For example, consider a business scenario where your partner might exploit your honesty for their advantage. Would you choose honesty if you knew the other side might betray you?

Also, consider the question of long-term perspectives. Are you ready to forgo immediate benefits to build stable, trusting relationships in the future? Is it worth risking your interests for a higher goal, such as strengthening the team or improving societal relationships?

The answers to these questions depend not only on your value system but also on the context of the situation. At the same time, such reflections help you understand yourself better and prepare for similar moral dilemmas in the future.

Thus, the Prisoner’s Dilemma is not just a test of rationality but also a measure of our moral maturity. By contemplating our actions and decisions, we not only improve our lives but also contribute to the creation of a more honest and responsible society.