Evolutionary psychology represents a unique direction of scientific thought that attempts to explain the structure of the human psyche through the lens of evolutionary processes. In the broadest sense, it is the science of how natural selection shaped our thoughts, emotions, and behavioral strategies over hundreds of thousands of years. Its key task is to identify universal psychological mechanisms that emerged as adaptations to the environment of our distant ancestors and continue to influence us today, even in a completely changed modern world.

The relevance of this approach is difficult to overestimate, as it offers a fundamentally new perspective on the nature of human behavior. Unlike classical psychology, which often treats the psyche as an abstract phenomenon, evolutionary psychology seeks concrete functional explanations: why we experience certain emotions, how our preferences are formed, and what unconscious algorithms govern our decisions. For example, modern models of mate selection turn out to be strikingly similar to the strategies that were optimal in the Pleistocene—men unconsciously assess signs of fertility, while women subconsciously seek signs of resources and status, directly reflecting the evolutionary logic of reproductive success.

The same applies to our fears—why do we instinctively fear snakes and spiders but not feel similar terror toward genuinely dangerous cars or electrical appliances? The answer lies in the so-called “Savanna Hypothesis”: our brains are better adapted to respond to threats from the ancient environment than to relatively new risks of modernity. Even complex social phenomena—from workplace hierarchies to racial prejudices—can be interpreted through the lens of evolutionary mechanisms of group behavior, which formed under conditions of competition between small tribes.

Thus, evolutionary psychology offers a powerful conceptual tool for understanding the most diverse aspects of human life—from intimate relationships to political processes. It does not merely describe how we behave but explains why our mental mechanisms are structured this way and not otherwise, opening new horizons for research in psychology, anthropology, and even economics.

Origins: Darwin and the First Theories

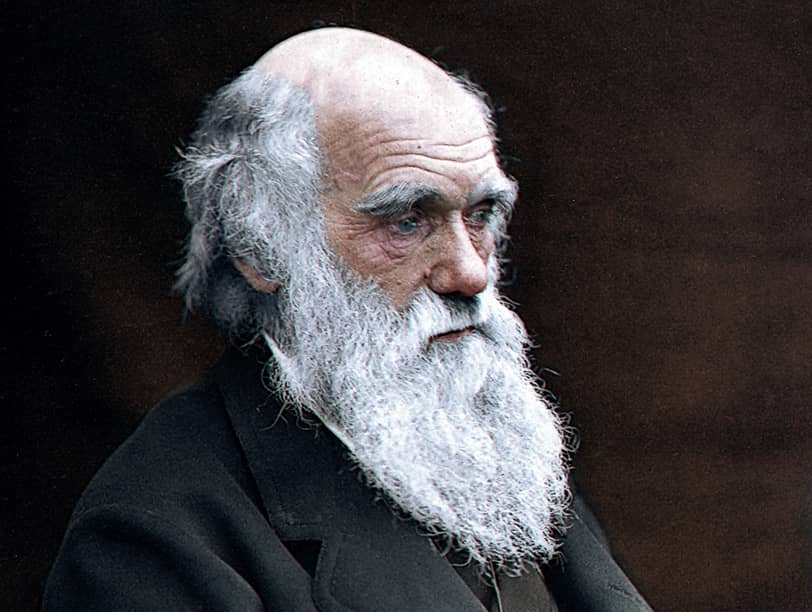

To understand how evolutionary psychology was formed, we must return to its roots—to those revolutionary ideas that overturned our understanding of humans and nature. In the mid-19th century, science stood on the brink of a monumental discovery: it turned out that the human psyche was not a divine gift but a product of millions of years of natural selection. This idea was so bold that it took decades to penetrate psychology. And it all began with the work of Charles Darwin—the scientist who changed our understanding of life.

Darwin did not merely explain the origin of species—he laid the foundation for understanding human behavior. His ideas about natural selection and sexual selection became the basis upon which evolutionary psychology later grew. However, the journey of these ideas in science was not easy: they were sometimes embraced with enthusiasm, sometimes rejected, and sometimes distorted beyond recognition. Let us trace how the key concepts emerged and why they did not immediately gain acceptance among psychologists.

Charles Darwin and His Contribution

When Darwin’s book “On the Origin of Species” was published in 1859, the world learned about the theory of natural selection—a mechanism that explained how complex organisms evolved from simple ones without any divine intervention. But few immediately realized that this theory had a direct bearing on the human psyche. Darwin himself only briefly mentioned the possible evolution of mental abilities, but his followers quickly understood: if the body changed under the influence of selection, then the mind must have developed according to the same laws.

Darwin took a decisive step in this direction in 1872 with the publication of “The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.” In this work, he systematically applied an evolutionary approach to psychology for the first time. Darwin demonstrated that our emotions are not cultural constructs but biological adaptations. For example, baring teeth in anger—seen in both humans and animals—has a common origin: it is a remnant of threatening behavior that helped our ancestors display aggression. Such observations became the first building blocks in the foundation of evolutionary psychology.

Herbert Spencer and “Social Darwinism”

Darwin’s ideas quickly spread beyond biology. The philosopher Herbert Spencer attempted to apply them to society, creating the concept of “Social Darwinism.” He believed that the same laws of natural selection operated in human society: the strong survive, while the weak are doomed to perish. Although this idea seemed like a logical extension of Darwin’s theory, it contained a dangerous oversimplification.

The problem was that Spencer and his followers applied biological laws to social processes without proper nuance. They justified social inequality, colonialism, and racial discrimination, calling it “natural selection in action.” Such interpretations discredited the evolutionary approach in the eyes of many scientists, especially in the early 20th century, when the memory of the abuses of “Social Darwinism” was still fresh.

Early 20th Century: Why Darwin’s Ideas Did Not Immediately Take Root in Psychology

The first decades of the 20th century marked a period of neglect for the evolutionary approach in psychology. There were several reasons for this. First, the ill-fated “Social Darwinism” created negative associations with any attempts to apply biological theories to humans. Second, psychology was dominated by behaviorism, which outright denied the role of innate factors, explaining all behavior solely through learning and environment.

Moreover, early attempts to create “evolutionary psychology” often suffered from speculation. Scientists constructed elegant theories about how certain behaviors might have helped our ancestors but could not support them with evidence. It was only in the second half of the 20th century, with the development of ethology, genetics, and cognitive science, that the evolutionary approach returned to psychology—this time with a serious methodological foundation. But for this to happen, science needed nearly a hundred years after the publication of “On the Origin of Species.”

Revival of Interest: The 1960s–1990s

After many years of neglect, the evolutionary approach to studying the human psyche experienced a true renaissance in the second half of the 20th century. This period became a time of bold theoretical breakthroughs and revolutionary discoveries that finally shaped evolutionary psychology as an independent scientific discipline. What happened during these three decades that made the scientific community reconsider the evolutionary roots of human behavior?

The 1960s–1990s were a golden age for interdisciplinary research. Advances in genetics, ethology, and cognitive science created a unique opportunity to synthesize biological and psychological knowledge. Scientists finally gained the tools to test bold hypotheses about the innate mechanisms of the psyche. It was during this period that the theoretical foundations were laid, upon which modern evolutionary psychology is still built today.

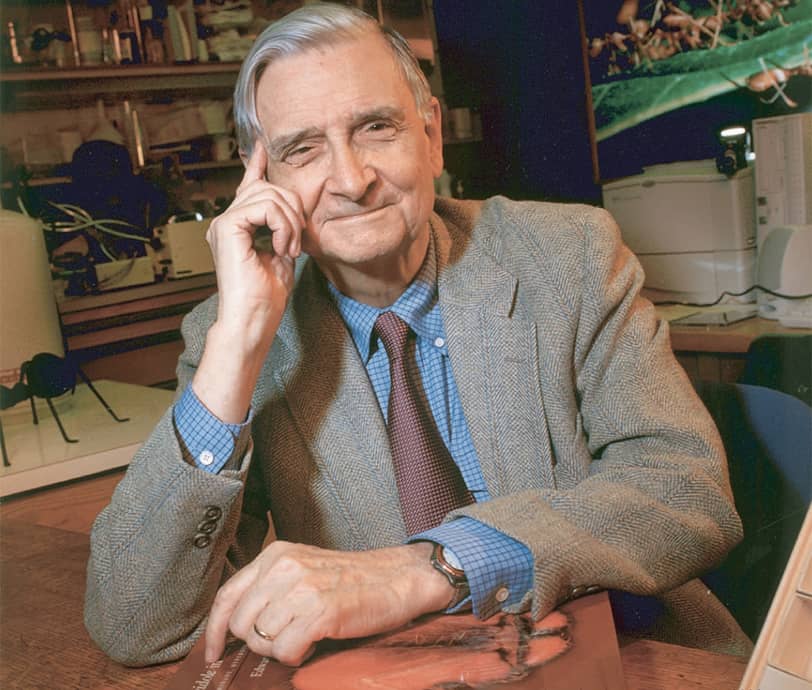

E.O. Wilson’s Sociobiology (1975) — A Bridge Between Biology and Behavior

The publication of Edward Osborne Wilson’s book “Sociobiology: The New Synthesis” in 1975 marked a turning point in the science of behavior. Wilson, a renowned entomologist who studied social insects, took a bold step—he extended the principles of evolutionary biology to all living beings, including humans. His key idea was that many aspects of social behavior have a genetic basis and are shaped by natural selection.

Although the term “sociobiology” was later partially replaced by “evolutionary psychology,” Wilson’s work played a crucial role. It rehabilitated the evolutionary approach to studying behavior after decades of behaviorist dominance. Particularly important was his analysis of altruism—behavior that seems evolutionarily disadvantageous. Wilson demonstrated that altruism could evolve through kin selection, explaining many paradoxes of social behavior.

John Tooby and Leda Cosmides – Founders of Modern Evolutionary Psychology

The real breakthrough in establishing evolutionary psychology as a distinct discipline is associated with the work of a married duo—psychologist Leda Cosmides and anthropologist John Tooby. In the late 1980s, they formulated the key principles that remain the foundation of this science today.

The concept of “modularity of mind” became their most significant contribution. Tooby and Cosmides proposed that the human brain is not a universal “general-purpose computer” but rather a set of specialized modules, each solving a specific adaptive problem during the Pleistocene era. For example, separate modules are responsible for facial recognition, deception detection, mate selection, or disease avoidance.

Their “hunter-gatherer hypothesis” explains why our brains are poorly adapted to the modern environment. According to this concept, core psychological adaptations formed during the period (approximately 1.8 million to 10,000 years ago) when humans lived in small hunter-gatherer groups. Evolution simply hasn’t had enough time to reconfigure our psyche for modern civilization, which explains many psychological issues—from fear of public speaking to struggles with self-control.

David Buss and Research on Sexual Strategies

The work of David Buss in the 1990s introduced rigorous empirical methods to evolutionary psychology and popularized it among the general public. His research on sexual strategies demonstrated how the principles of sexual selection, first outlined by Darwin, manifest in modern human behavior.

Buss and his colleagues conducted large-scale cross-cultural studies spanning 37 countries and discovered striking consistency in male and female preferences. For example, men universally value youth and physical attractiveness (indicators of fertility) in partners, while women prioritize resources and social status (ability to provide for offspring). These differences are perfectly explained by parental investment theory: since women biologically invest more in offspring (pregnancy, breastfeeding), they are more selective in choosing mates.

Buss’s most valuable contribution was the development of “strategic pluralism” theory—the idea that people employ different reproductive strategies depending on circumstances. For instance, men may simultaneously pursue both short-term and long-term mating strategies, using different approaches in each case. These studies not only confirmed evolutionary theory’s predictions but also demonstrated its explanatory power in the realm of human relationships.

Core Principles of Evolutionary Psychology

Evolutionary psychology is built upon several fundamental principles that distinguish it from other branches of psychological science. These principles are not just theoretical constructs—they help explain why our psyche is structured the way it is and how ancient adaptations continue to influence our behavior in the modern world. Understanding these foundations offers a fresh perspective on seemingly familiar psychological phenomena.

Unlike classical psychology, which often treats the mind as a “blank slate,” the evolutionary approach posits that our brain is a complex product of millennia of natural selection. Every feature exists for a reason—because it helped our ancestors survive and reproduce. Let’s examine in detail three key principles that form the basis of this revolutionary paradigm.

Psychology as Adaptation

The core of the evolutionary approach is the idea that most of our psychological traits are adaptations—beneficial traits shaped by natural selection. Take fear, for example. Why do we instinctively fear heights, darkness, or snakes? Because these fears protected our ancestors from real dangers. Those who weren’t afraid of heights fell off cliffs more often; those who didn’t fear snakes died more frequently from bites. As a result, the genes of “cautious” individuals spread through the population.

The same applies to complex emotions like jealousy or love. Jealousy is a mate-guarding mechanism that prevented the loss of valuable reproductive resources. Love, from an evolutionary perspective, is an attachment mechanism ensuring long-term care for offspring. Even our preference for sweet and fatty foods is an adaptation to an environment where calories were scarce, not a problem.

Parental Investment Theory and Sexual Selection (Trivers, 1972)

In 1972, Robert Trivers formulated the theory of parental investment, which became a cornerstone of evolutionary psychology. Its essence is simple: the sex that invests more resources in offspring (typically females) will be more selective when choosing a mate. In humans, women bear significantly greater biological costs (pregnancy, childbirth, breastfeeding) than men, explaining many gender differences in behavior.

This theory perfectly explains why men, on average, are more risk-prone and competitive—success in securing resources and status increased their reproductive chances. Women, on the other hand, evolved to be more selective in choosing partners, as a poor choice could cost them nine months of pregnancy and years of raising a child without proper support. These differences persist even today, though modern society offers far more opportunities to shift traditional gender roles.

The Savanna Hypothesis – Why Are We Poorly Adapted to the Modern World?

One of the most intriguing principles of evolutionary psychology is the Savanna Hypothesis, also known as the “evolutionary mismatch” hypothesis. According to this concept, our brains are adapted to the conditions of the Pleistocene (approximately 2.5 million to 11,000 years ago), when core psychological adaptations emerged. The problem is that over the last 10,000 years (and especially the last 200 years), the environment has changed dramatically, while our psyche has not.

This explains many modern struggles. Why do we crave sweets despite knowing they’re unhealthy? Because in calorie-scarce environments, a preference for high-energy foods was advantageous. Why is it hard to resist social media temptations? Because our brains are evolutionarily wired to seek social information and approval—crucial for survival in small groups. Even our political biases often stem from ancient “us vs. them” mechanisms that function poorly in a globalized world.

The Savanna Hypothesis helps explain why modern humans often feel “out of place”—we live in a world our psyche was never designed for. This doesn’t mean we can’t adapt to new conditions, but it clarifies why doing so requires such effort and frequently leads to psychological challenges.

Modern Research and Discoveries

Today, evolutionary psychology is experiencing a period of rapid development, supported by the latest advances in neuroscience, genetics, and anthropology. Modern technologies allow scientists to test hypotheses that just 30 years ago seemed purely speculative. We stand on the brink of a revolution in understanding how millennia of evolution continue to influence our behavior in the age of digital technology and globalization.

The synthesis of evolutionary psychology with other disciplines is particularly exciting. Researchers can now literally “peer into” the brain and observe how ancient neural circuits respond to modern stimuli. At the same time, there is growing recognition of the complex interplay between biological predispositions and cultural influences—helping to avoid oversimplified interpretations of human behavior.

Neuroscience and Evolutionary Psychology

Modern neuroimaging techniques (fMRI, PET, EEG) have led to a remarkable discovery: our brains have indeed retained ancient mechanisms that continue to operate on the same principles as those of our distant ancestors. For example, when we see the face of a potential partner, the same brain regions (amygdala, ventral tegmental area) activate as those responsible for assessing reproductive value in early humans.

Research on fears is especially revealing. It turns out that responses to evolutionarily ancient threats (snakes, spiders) are processed through faster subcortical pathways than responses to modern dangers (weapons, electricity). This explains why phobias are more commonly associated with ancient threats—our brains are literally “hardwired” to recognize them quickly.

Culture vs. Instincts – Which Has a Stronger Influence on Behavior?

One of the hottest debates in modern science concerns the balance between biological and cultural influences on human behavior. Cross-cultural studies reveal a fascinating pattern: while basic psychological mechanisms are indeed universal, their manifestations can vary significantly across cultures.

A striking example is mate preferences. Although men in all cultures tend to value youth and attractiveness, while women prioritize resources and status, the degree of these differences depends on social conditions. In societies with high gender equality, the differences diminish but do not disappear entirely. This points to a complex interaction between instinctual programs and cultural norms.

Criticism and Limitations of Evolutionary Psychology

Despite impressive progress, evolutionary psychology faces significant criticism. One major issue is so-called “just-so stories”—hypothetical adaptations. Critics rightly point out that it’s easy to devise evolutionary explanations for nearly any behavior, but far harder to prove that it was truly adaptive in the past.

For instance, some researchers once claimed that women’s preference for the color pink was an adaptation for berry gathering. However, historical studies show that gender-based color preferences are a recent cultural phenomenon. This underscores the importance of rigorously testing evolutionary hypotheses.

Equally contentious are debates about nature vs. nurture. Modern epigenetic research demonstrates that even clearly innate tendencies can manifest differently depending on the environment. For example, a genetic predisposition to aggression may or may not materialize based on upbringing.

These debates do not undermine the evolutionary approach—on the contrary, they help refine it, making it more precise and scientifically robust. As leading researchers note, the future of evolutionary psychology lies in integration with other disciplines and the development of stricter hypothesis-testing methods. Only then can we distinguish truly universal psychological mechanisms from culturally specific phenomena.

Where is Evolutionary Psychology Applied?

The theoretical discoveries of evolutionary psychology find surprisingly wide applications in real life—from personal relationships to business and mental health. Understanding our ancient psychological programming not only helps explain behavior but also allows us to consciously use this knowledge to improve quality of life. Let’s examine how the “user manual” of the human psyche, written by evolution, operates in modern conditions.

Psychology of Relationships (Why We Choose Certain Partners)

Evolutionary psychology provides an remarkably accurate map of our romantic preferences. Numerous studies confirm: when choosing a partner, we unconsciously look for signs of evolutionary advantage. For men, these signals include:

- Waist-to-hip ratio of about 0.7 in women (indicator of optimal estrogen levels)

- Clear skin and shiny hair (markers of health)

- Symmetrical facial features (sign of good genes)

Women, on the other hand, subconsciously evaluate:

- Social status and resources (ability to provide for offspring)

- Physical strength and V-shaped torso (testosterone indicator)

- Reliability and willingness for long-term commitment

Interestingly, these preferences persist even in the age of gender equality. For example, successful businesswomen in dating profiles still more often express desire to find a partner “even more successful” than themselves. Evolutionary psychology explains this not through social stereotypes but through deeply rooted reproductive strategies.

Marketing and Advertising (How Brands Exploit Our Instincts)

Advertising professionals have long intuitively used evolutionary mechanisms—now they do so consciously:

- Scarcity principle (“Only 3 items left!”)—activates our ancient fear of missing rare resources

- Use of status signals – luxury watches or cars are presented as modern equivalents of alpha-male position in the pack

- Appeal to sweet/fatty foods – dietary preferences formed in calorie-scarce environments

- “Rose-colored glasses” effect – cosmetics ads exploit our hypersensitivity to signs of youth

Social media platforms are particularly illustrative: their design exploits our need for social approval (analogous to tribal status) through likes and comments. The “like” button triggers dopamine release—the same mechanism that drove our ancestors to seek approval from their group.

Psychotherapy—Can We “Rewrite” Evolutionary Programs?

Modern therapy increasingly considers evolutionary roots of problems:

- Anxiety disorders: understanding that anxiety is a “false alarm” of ancient warning systems helps in cognitive-behavioral therapy

- Depression: some forms may be adaptive “braking” response to insurmountable problems (analogous to energy conservation in unfavorable periods)

- Eating disorders: recognizing our calorie craving as a relic of scarcity helps combat overeating

A crucial breakthrough is the concept of “evolutionary mismatch”: many psychological problems arise from conflict between ancient programs and modern environment. For example:

- Fear of public speaking – exaggerated response to danger of tribal judgment

- Procrastination – result of orientation toward short-term gains in uncertain conditions

While we can’t completely “rewrite” evolutionary programs, we can redirect them. Cognitive-behavioral therapy essentially teaches the neocortex (new brain areas) to “translate” and regulate signals from older structures. It’s like learning to use an ancient operating system by installing a modern interface.

Conclusion

Evolutionary psychology continues to develop rapidly, opening new horizons in understanding human nature. Modern technologies such as genetic mapping and big data analysis are taking research to a fundamentally new level. Scientists can now track how specific genetic variations influence behavioral patterns, while large-scale databases enable identification of universal psychological mechanisms by comparing thousands of cultures worldwide. For example, machine learning studies already help uncover non-obvious connections between ancient adaptations and modern social phenomena—from consumer habits to political preferences.

At the same time, the evolutionary approach is not merely a theoretical construct—it offers practical tools for solving real-world problems. The understanding that many of our psychological difficulties stem from conflicts between ancient “hardwiring” and modern environments is transforming approaches in education, psychotherapy, and even urban planning. Future cities may be designed considering our innate need for green spaces and safe shelters, while educational programs could account for natural mechanisms of children’s cognition shaped by tribal living conditions.

However, the value of evolutionary psychology lies not only in its applied potential but also in its unique ability to integrate disparate facts about humans into a coherent picture. It serves as a bridge between biology and social sciences, explaining why human behavior retains certain universal traits despite cultural influences. This approach does not negate the role of upbringing or individual experience but clearly demonstrates: we cannot fully understand ourselves while ignoring millennia of evolutionary heritage.

Ultimately, evolutionary psychology provides something greater than just scientific explanations—it offers a new way of self-discovery. Recognizing that our fears, desires, and decisions echo the experiences of countless generations allows us to approach human nature with deeper understanding—not as a set of random traits but as a complex yet logical system of adaptations. And although many questions remain unanswered, one thing is already clear: the evolutionary perspective has become an integral part of the eternal quest to answer the question, “What makes us human?”