The Zeigarnik effect is not just an intriguing psychological phenomenon, but a powerful mechanism that daily influences our attention, motivation, and even emotional state. As research by Bluma Zeigarnik and subsequent work in cognitive psychology has shown, our brains are wired in such a way that unfinished tasks create a unique tension, compelling us to return to them again and again. This explains why we might forget about a completed project but remember for months that we “never finished reading” a book or left a task incomplete.

However, this effect is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it helps maintain focus on important tasks, nudges us to complete what we’ve started, and is even used in marketing, education, and art to sustain attention. On the other hand—if unfinished tasks pile up—they become a source of stress, anxiety, and mental overload. The constant feeling of “something left undone” is exhausting, reduces productivity, and prevents us from enjoying the present moment.

The key to managing the Zeigarnik effect is mindfulness. Instead of letting unfinished tasks endlessly spin in our heads, we can harness this mechanism to our advantage: for example, by deliberately breaking large tasks into stages, leaving a slight sense of incompleteness to maintain motivation. But it’s equally important to “close the loop” in time—either by completing tasks or consciously letting them go if they’ve lost relevance. Simple techniques like the two-minute rule or list prioritization help reduce psychological strain and regain control over our attention.

Ultimately, the Zeigarnik effect reminds us: productivity is not just about action but also about the ability to negotiate with our own brains. By learning to balance healthy tension from incompleteness and timely completion, we can not only work more efficiently but also live more peacefully. So, what unfinished tasks are bothering you? Perhaps it’s time to either finish them or—and this is also an important skill—simply cross them off the list. After all, as writer G.K. Chesterton said, “The ability to finish things is a luxury only the strong can afford.”

What is the Zeigarnik Effect?

Imagine you’re watching an exciting TV series, and at the most intense moment, the episode cuts off at the climax. What do you feel? A burning desire to know what happens next! Or another example: you start an important project but put it off for later—yet thoughts about it keep haunting you even while you’re doing other things. These familiar situations perfectly illustrate the Zeigarnik effect – a psychological phenomenon that explains why unfinished actions are remembered better than completed ones.

This effect is not just an interesting observation but a powerful mechanism of our memory and motivation. It influences how we learn, work, and even how we perceive art and advertising. But to understand it more deeply, let’s go back to its origins—to a discovery made nearly a hundred years ago.

The Discovery: The Experiment with Waiters and Unfinished Orders

In 1927, a young Soviet psychologist, Bluma Vul’fovna Zeigarnik, a student of the famous Kurt Lewin, conducted a simple yet brilliant experiment. She noticed that waiters in cafés perfectly remembered unpaid orders but immediately forgot them as soon as the customer paid. To test this pattern, Zeigarnik organized a series of laboratory experiments.

Participants were given various tasks (such as puzzles or crafts), but they were intentionally interrupted mid-process. Later, it turned out that people remembered interrupted tasks 90% better than those they had completed! This became proof: unfinished actions create a special kind of “tension” in the brain, forcing us to mentally return to them again and again.

Scientific Definition: The Brain Remembers Interrupted Actions Better

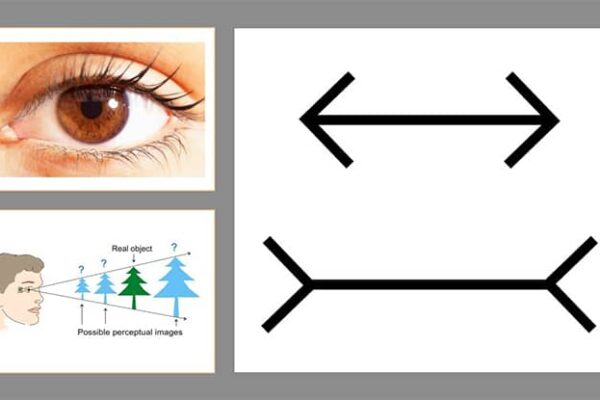

From a scientific standpoint, the Zeigarnik effect is the tendency of human memory to retain information about unfinished tasks longer and more clearly than about completed ones. Why does this happen?

- The brain perceives unfinished tasks as an “open loop.” As long as a task remains unresolved, our mind automatically marks it as important to keep it in sight. It’s like a “background program” that keeps running even when we switch to other tasks.

- Emotional imprint. Interrupted actions often cause mild discomfort (sometimes we don’t even realize it). It’s this feeling of “something missing” that makes us remember the task.

- An evolutionary mechanism. Scientists suggest that this is how the brain protected us from dangers: for example, an unfinished hunt or an incomplete shelter required heightened attention for survival.

Connection to Kurt Lewin’s Theory of “Quasi-Needs”

Zeigarnik didn’t work in a vacuum – her discovery became part of Kurt Lewin’s field theory, one of the foundations of modern social psychology. Lewin introduced the concept of “quasi-needs” – temporary mental tensions that arise when we set a goal.

How does it work? Imagine you decide to cook dinner. At that moment, a “tension” – a quasi-need – forms in your mind. Until the dish is ready, the tension remains, motivating you to act. Once the task is completed, the tension disappears, and the brain “lets go” of it.

-

Interrupted = Important. If an action is left incomplete (e.g., you run out of ingredients), the tension doesn’t go away. This explains why we fixate on such tasks: the brain literally demands “closure.”

The Zeigarnik effect became experimental confirmation of these ideas, showing that incompleteness creates a lasting trace in memory – and we can use this knowledge in everyday life, psychology, education, or business.

Why Is This Important Today?

The Zeigarnik effect is not just a textbook theory. It helps us understand:

- Why we procrastinate yet keep worrying about unfinished tasks;

- How TV shows and advertisements manipulate our attention;

- Why a “to-do list” sometimes causes more stress than it helps.

By recognizing these mechanisms, we can stop fighting ourselves and start using them mindfully—for example, by breaking big tasks into stages or artificially creating “incompleteness” for motivation. But more on that in the next sections of the article.

How Does the Zeigarnik Effect Work?

Have you ever noticed how difficult it is to get an unfinished project or an interrupted conversation out of your head? This isn’t just a coincidence—it’s the Zeigarnik effect in action, a powerful psychological mechanism literally “hardwired” into our thinking. But what exactly happens in our brain at this moment? Why do unfinished tasks have such power over our attention?

To understand this, we need to look “under the hood” of our psyche. The Zeigarnik effect isn’t just an abstract concept but a very specific process involving certain brain regions, emotional reactions, and even evolutionary survival mechanisms. Let’s break down exactly how it works.

Neuropsychology: The Role of the Prefrontal Cortex and Memory

In the brain, the Zeigarnik effect is governed by a complex system of interactions between different regions. The prefrontal cortex—the brain’s “command center” responsible for planning and attention—plays the main role here. When we start a task, this area activates and creates a sort of “mental bookmark.”

But what happens if the task is interrupted? fMRI studies show that in this case:

- The prefrontal cortex continues sending alarm signals.

- The hippocampus (responsible for memory) marks the task as “priority.”

- Dopamine levels (the motivation hormone) remain elevated until the task is completed.

Interestingly, this mechanism is very similar to a GPS system that constantly reminds us: “You have not yet reached your destination.” The brain literally cannot calm down until it receives a completion signal.

Psychological Mechanism: Unfinished Tasks Create Tension That Motivates Completion

From a psychological perspective, the Zeigarnik effect can be compared to a stretched rubber band—the longer a task remains unresolved, the stronger the “tension.” Psychologists call this phenomenon “cognitive dissonance of incompleteness.”

Here’s how it works step by step:

- We start a task and mentally allocate “mental space” for it.

- When interrupted, an imbalance arises between the expected and actual outcomes.

- Our mind perceives this as a threat to integrity (since we’re programmed to prefer completeness).

- Tension arises, motivating us to eliminate the imbalance.

This mechanism is so strong that research shows people are willing to expend extra effort just to “check the box,” even if the task itself is no longer relevant.

Example: Why Do TV Shows Leave Viewers at the Climax?

A classic example of the Zeigarnik effect in pop culture is the famous cliffhangers in TV series. When an episode cuts off at the most exciting moment, it:

- Creates artificial “mental tension.”

- Activates the same neural pathways as unfinished tasks in real life.

- Increases the likelihood that viewers will return to watch more.

Marketers and screenwriters have long used this technique. Statistics show that series with cliffhangers have 15-20% more views of subsequent episodes. What’s interesting is that the strength of the effect doesn’t depend on content quality—even a mediocre series can hold attention thanks to well-crafted unresolved plotlines.

This same principle works in:

- Advertising (“To be continued…”).

- Social media (“1 of 5 tips…”).

- Even music (unexpected pauses or abruptly ending melodies).

By understanding how the Zeigarnik effect operates at the neurobiological and psychological levels, we can not only explain many everyday phenomena but also learn to harness this mechanism for our benefit—to boost productivity, improve memory, or even create more engaging content.

Manifestations of the Zeigarnik Effect in Everyday Life

The Zeigarnik effect isn’t just an abstract psychological concept. It manifests in various aspects of our daily lives, often without our conscious awareness. From mundane situations to global marketing strategies – unfinished actions exert an astonishingly powerful influence on our behavior and emotions.

Why do certain things literally stick in our minds? How do companies use this knowledge to attract customers? And why does unfinished art sometimes move us more than perfected works? Let’s examine specific examples of how the Zeigarnik effect operates in the real world.

Procrastination: Why Do Delayed Tasks Get “Stuck” in Our Heads?

The phenomenon of procrastination is closely related to the Zeigarnik effect. When we postpone an important task, our brain continues to consider it relevant, creating constant background anxiety. Here’s how it works:

- Unfinished tasks create “mental hooks” that cling to our attention.

- Even when engaged in other activities, we expend part of our cognitive resources tracking postponed tasks.

- Research shows that people with many “open loops” experience more stress and concentration difficulties.

Paradoxically, it’s precisely important tasks (those we most often postpone) that create the strongest Zeigarnik effect. The more significant a project is to us, the more mental tension it generates when delayed.

Study and Work: How Partially Completed Projects Affect Concentration

In professional and academic settings, the Zeigarnik effect manifests particularly vividly:

- Unfinished projects reduce overall productivity by 15-20% (according to research data).

- Interrupted tasks create a “cognitive residue” effect, hindering full focus on new tasks.

- Partially completed assignments are often remembered better than finished ones (which benefits learning).

An interesting fact: many successful people intuitively use this effect by ending their workday mid-sentence or mid-task. This creates a “mental hook” that helps them re-engage with work faster the next day.

Marketing and Advertising: How Brands Leverage Incompleteness

Marketers have long employed the Zeigarnik effect. Here are the most common techniques:

- Serial content: “To be continued,” “Part 1 of 5.”

- Unfinished stories in advertisements that make viewers seek continuations.

- Time-limited offers creating a sense of incomplete action.

- Games and apps with progress bars and uncompleted achievements.

Research shows such strategies increase customer engagement by 30-40%. For example, serial blog posts receive 2.5 times more website clicks.

Art and Creativity: Why Unfinished Works Evoke Stronger Emotions

In the art world, the Zeigarnik effect explains many perception paradoxes:

- Unfinished works (like Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony”) often elicit stronger responses.

- Open endings in literature are remembered better and discussed more actively.

- Sketches and drafts by great masters are sometimes valued higher than completed works.

- Contemporary art frequently uses incompleteness as an artistic device.

Psychologists explain this because unfinished works:

- Activate the viewer’s/reader’s imagination.

- Create space for personal interpretation.

- Generate a desire to “complete,” which strengthens emotional connection.

This phenomenon is so powerful that some artists deliberately leave works unfinished to enhance their impact on audiences.

Understanding these manifestations of the Zeigarnik effect allows us to be more mindful of our time, attention, and emotions – both in personal life and professional activities. The key is remembering that incompleteness can be both a source of stress and a powerful creative tool.

How to Use the Zeigarnik Effect to Your Advantage?

The Zeigarnik effect isn’t just a psychological phenomenon that explains our behavior. It’s a powerful tool that, when used skillfully, can become your ally in achieving goals. By understanding its mechanism, you can consciously apply its principles to boost productivity, improve memory, and reduce stress.

Many successful people intuitively use this effect in their daily lives. The good news — now you can do it consciously too. Let’s explore specific strategies that will help turn this psychological feature of your brain into a personal productivity assistant.

Boosting Productivity

The “Start But Don’t Finish” Method to Combat Procrastination

This paradoxical method works surprisingly well. Instead of putting off starting a difficult task, try doing the exact opposite:

- Begin working on the project but deliberately interrupt yourself at the most interesting point.

- Take the first steps: write the first paragraphs of text, create a presentation structure, prepare materials.

- Stop when you feel you’ve gotten into the workflow.

Why does this work? Your brain will remember the unfinished action as an “open loop” and will strive to complete it. The next day, you’ll find it much easier to return to the task — the mental tension itself will push you to continue.

Breaking Tasks Into Stages to Maintain Motivation

Large projects often seem daunting, causing procrastination. The Zeigarnik effect offers an elegant solution:

- Divide a major task into 5-7 clear stages.

- Take a short pause after completing each stage.

- Consciously note the incompleteness of the next stage.

This strategy creates a constant “wave” of motivation — when you finish one stage, you already feel drawn to start the next. It’s like a TV series with engaging episodes — you always want to know what happens next.

Learning and Memorization

Interrupting Study Sessions for Better Retention

The traditional approach to learning suggests completing topics or chapters. However, the Zeigarnik effect offers a more effective strategy:

- Plan study sessions so you interrupt yourself mid-topic.

- The optimal time for a break is when you’ve already grasped the material but haven’t exhausted your interest.

- Before pausing, formulate a specific question you want to answer when continuing.

This method improves information retention by 20-30% because the brain continues processing the material in the background. This explains why students who study with breaks often show better results than those trying to “learn everything at once.”

Personal Effectiveness

Consciously Completing Tasks to Reduce Anxiety

While the Zeigarnik effect is useful for motivation, sometimes we need the opposite — the ability to “close” tasks to free up mental space:

- Create a completion ritual: physically cross out completed tasks, close tabs, mark items as “done.”

- For tasks you decide not to complete, hold a conscious “closing ceremony” — write down the reasons for abandoning them and mentally say goodbye.

- At the end of the day, make a list of “closed loops” — this will reduce background anxiety.

Interesting fact: research shows that simply writing down completed tasks reduces stress levels by 15-20%. Your brain receives a clear signal that the task no longer requires attention.

These methods can be combined and adapted to your needs. For example, a writer might use the “start but don’t finish” strategy for each book chapter, a student might interrupt study sessions before breaks, and a manager might break large projects into stages with clear interruption points. The key is understanding the basic principle: our attention naturally strives to complete what’s been started, and this feature can be used consciously.

When the Zeigarnik Effect Becomes a Problem?

The Zeigarnik effect, which normally helps us complete tasks, can turn into a true mental saboteur when it gets out of control. How does this useful psychological mechanism become a source of constant stress? Why does the same tension that should motivate us start working against us?

When the number of unfinished tasks exceeds a critical threshold, our brain literally becomes overloaded with “open loops.” It’s like a computer running too many programs simultaneously — the system starts to freeze. Let’s examine how to recognize this problem and regain control over our productivity.

Chronic Stress from Accumulated Unfinished Tasks

Uncompleted tasks create a “background noise” effect in our psyche:

- Each unresolved problem consumes part of our cognitive resources.

- The brain constantly scans the list of unfinished tasks, even during rest.

- Research shows people with 5+ “open loops” have 30% higher cortisol levels.

Warning signs:

- Constant feeling of “forgetting something.”

- Trouble falling asleep due to “replaying” tasks.

- Irritability without obvious reasons.

- Decreased productivity in the afternoon.

Psychologists call this “unfinished gestalt” — when the psyche spends more energy tracking problems than solving them.

Obsessive Thoughts About Unfinished Business (“Open Loops” Syndrome)

The Zeigarnik effect becomes pathological when:

- Thoughts about unfinished tasks occur more than 5-7 times per hour.

- You catch yourself constantly “mentally returning” to the same tasks.

- Feelings of guilt about postponed matters emerge.

Particularly dangerous are:

- Long-term unresolved issues (unpaid debts, unfulfilled promises).

- Emotionally charged unfinished business (unfinished conversations, unresolved relationships).

- Multi-year “ghost projects” (unfinished book, unrealized business idea).

Such “loops” can linger in the psyche for years, creating constant background tension.

How to Fight Back: Completion Techniques (2-Minute Rule, Priority Lists)

Effective “loop closing” strategies:

2-Minute Rule (from GTD methodology):

- If a task takes less than 2 minutes — do it immediately.

- Prevents accumulation of micro-tasks that create “mental clutter.”

- Examples: replying to a short email, calendar entry, quick phone call.

ABCDE Priority System:

- A: Critical tasks (serious consequences if not done).

- B: Important but not urgent.

- C: Pleasant but optional.

- D: Delegable.

- E: Eliminable tasks.

- Daily, complete at least 1 A-category task.

Mental Closure Ritual:

-

At day’s end, list all unfinished tasks.

-

For each, note:

-

Concrete next step.

-

Deadline.

-

Priority.

-

-

Mentally “hand off” these tasks to your future self.

Written Completion Technique:

- For tasks you decide not to complete, write a brief explanation.

- Add “I consciously close this loop [date].”

- Burn or tear the paper (symbolic act of completion).

Interesting fact: Stanford University research showed that people regularly practicing “loop closure” demonstrate 40% lower stress levels and 27% higher productivity.

It’s important to understand: the Zeigarnik effect is a tool. Like a hammer, it can help build a house or accidentally break a window. Conscious management of “open loops” preserves this mechanism’s benefits while avoiding its destructive impact on mental health.

Conclusion

The Zeigarnik effect is an amazing mechanism of our psyche that, like two-faced Janus, can be both our ally and a hidden source of stress. Unfinished actions influence our attention, motivation, and emotional state — from everyday situations to global marketing strategies. This phenomenon, discovered nearly a century ago, remains a relevant tool for understanding human behavior even in the digital age.

The main secret to working with the Zeigarnik effect lies in conscious balancing. On one hand, we can artificially create “controlled incompleteness” — breaking large projects into stages, interrupting study sessions at interesting points, or using serial techniques to maintain interest. These methods help sustain motivation and improve retention. On the other hand, it’s important to regularly “close loops” — either completing or consciously abandoning tasks using techniques like the two-minute rule or priority systems. This balance preserves the effect’s benefits while avoiding its destructive influence on our mental wellbeing.

As practice shows, most of us intuitively feel this effect’s operation in our lives. Perhaps right now you’re recalling some of your own “open loops” — an unfinished book, postponed repairs, unrealized ideas, or incomplete conversations. This is an excellent moment for reflection: which of these unfinished matters are truly worth completing, and which may have lost relevance and deserve conscious “closure”? Answering this question could be the first step toward more mindful management of your attention and productivity. After all, as psychologist William James said, “wisdom is the art of knowing what to overlook.” The Zeigarnik effect gives us tools to develop precisely this kind of wisdom in daily life.