Game Theory is a mathematical discipline that studies strategic interactions between rational players, examining how participants make decisions considering the possible actions of others and striving to maximize their own benefits. Despite its mathematical nature, it is increasingly used to understand how people make decisions in various real-life situations. Its concepts have become essential not only in economics or politics but also in psychology, sociology, management, marketing, and even in child-rearing.

In today’s world, we constantly encounter situations that can be described using the language of game theory:

- Relationships with others: Should one compromise in a conflict?

- Financial decisions: Invest money now or wait for a better opportunity?

- Social situations: Act independently or rely on a team?

People often act unconsciously, yet their actions follow a certain logic that can be analyzed through game theory strategies. This helps better understand one’s own behavior and predict the actions of others. Knowledge of this theory makes life more efficient, helping to avoid conflicts, achieve goals, and build relationships.

What is Game Theory?

Game theory is a discipline at the intersection of mathematics, economics, and psychology that examines how rational players make decisions in situations where their actions are interdependent. Unlike ordinary scenarios where an individual acts in isolation, in games, every decision depends on the expected reactions of other participants.

The essence of game theory lies in studying strategies that help maximize outcomes in any situation. For example, in negotiations, conflicts, or partnerships, each party tries to achieve its goals while considering that others are doing the same. Analyzing such interactions reveals optimal ways to act.

Definitions and Key Concepts: Players, Strategies, and Payoffs

- Players

Players are the participants of the game who interact in a specific environment by making decisions. A player can be:- an individual (e.g., in negotiations);

- a group of people (a team in a sports competition);

- an organization or country (in international conflicts).

Each player has a specific goal they strive to achieve using their available resources and strategies.

- Strategies

Strategies are sets of actions that a player can choose in a particular situation. These can be:- Dominant strategies – choices that always yield the best result, regardless of others’ actions.

- Mixed strategies – combinations of several options where the choice is made randomly.

- Payoffs

Payoff refers to the outcome of the game for each player. It is determined not only by the chosen strategy but also by the actions of other participants. Payoffs can be:- Absolute – clearly defined benefits (money, points, resources).

- Relative – an advantage over other players.

Importantly, one player’s success does not always mean another’s loss. In many situations, a compromise that benefits both parties is possible.

Types of Games: Cooperative and Non-Cooperative

- Cooperative Games

In cooperative games, players can join forces to achieve a common goal. Here, not only personal gains but also the distribution of results among all participants are important.- Example: Two companies agree to jointly produce a product to reduce costs.

Features:

- Participants can make agreements and arrangements.

- The primary goal is to maximize overall payoff.

- Used in business, international negotiations, and social projects.

- Non-Cooperative Games

Non-cooperative games assume that each player acts independently, aiming to maximize their own benefit. Trust or shared interests are absent in such scenarios.- Example: Competition between two firms in the same market.

Features:

- Each player focuses only on their own interests.

- Agreements and cooperation are unattainable or irrelevant.

- Often used to analyze conflicts, competitions, and elections.

Nash Equilibrium: How People Make Decisions in Complex Situations

Nash equilibrium is a state in a game where each player chooses the optimal strategy, taking into account the choices of others. In this state, no one has an incentive to change their actions, as it would not improve their outcome.

Explanation

Imagine two competitors selling the same product. If one lowers the price, the other will be forced to follow suit to retain customers. The Nash equilibrium in this situation could involve setting a price that minimizes losses for both.

Characteristics of Nash Equilibrium

- Each player selects the best strategy considering the actions of others.

- No one benefits from unilaterally changing their strategy.

- The equilibrium can be:

- Unique – only one outcome;

- Multiple – several equilibria.

Example: The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Two suspects are held in separate cells. They have two options: confess or stay silent.

- If both remain silent, they receive minimal punishment.

- If one confesses while the other remains silent, the betrayer gets a reduced sentence, and the silent one receives maximum punishment.

- If both confess, they receive moderate punishment.

The Nash equilibrium here is when both confess, although this is not the best outcome for either.

Practical Significance of Nash Equilibrium

This principle applies in business, politics, marketing, and psychology. It helps understand how people make decisions in competitive environments and achieve stable outcomes.

Psychological Dimension of Game Theory

Game theory, while rooted in mathematics, is closely linked to psychology, as most strategic decisions people make are driven not only by rational calculations but also by emotions, values, and personal traits. Human decisions are rarely entirely objective since they are shaped by internal characteristics, experience, and social influences.

The Influence of Personality Factors on Strategy Choice

Every individual is unique, and their strategic decisions depend on personality traits such as:

- Risk tolerance: Some people are inclined toward risk, while others prefer stability.

Example: In a game where there’s a chance to win big or avoid losses, risk-takers will choose the former, while cautious players will opt for the latter. - Empathy: The ability to understand others’ feelings and intentions. People with high empathy levels are more likely to choose cooperative strategies.

Example: In a cooperative game, an empathetic person is more likely to agree to a compromise than a self-centered one. - Motivation: The drive to achieve benefits or avoid losses.

People focused on achievement may act more aggressively than those who avoid risks.

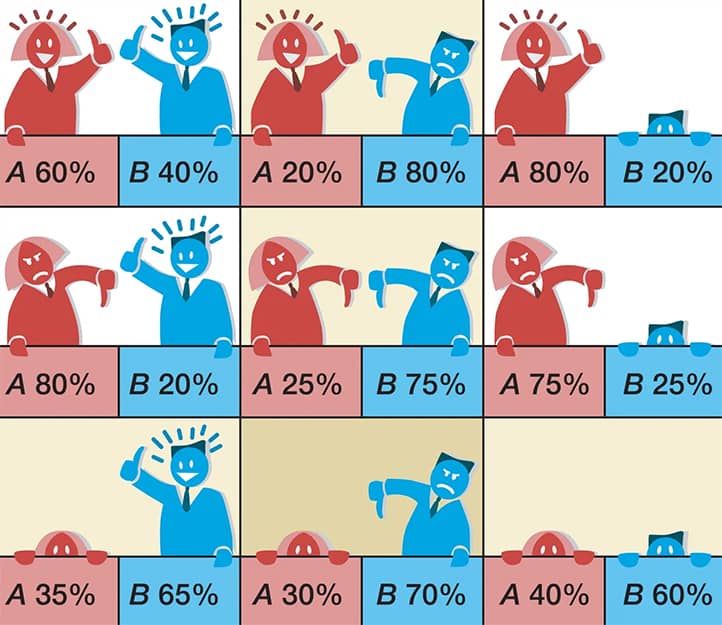

Personality Types and Strategy Choices

- Extroverts are more likely to choose cooperation, as they value social interaction.

- Introverts may prefer individual decisions, avoiding excessive interaction.

- Neurotics tend to overanalyze risks, which can lead to indecision or avoidance of the game.

Understanding a player’s personality traits helps predict their behavior and use this knowledge to build one’s own strategy.

The Role of Emotions: Are We Always Rational?

Game theory assumes that people act rationally, striving to maximize benefits. However, emotions often disrupt this balance.

Negative Emotions

- Anger: Can lead a person to choose a strategy of punishing another player, even if it goes against their own interests.

Example: In a conflict, a person might choose an action that harms both parties just to “teach a lesson” to the opponent. - Fear: Encourages avoidance of risky strategies, even if they are potentially beneficial.

Positive Emotions

- Trust: Encourages cooperation and a willingness to compromise.

- Joy: Increases the willingness to take risks, as the person feels optimistic.

Emotional states also affect strategic thinking. For example, under stress, people often choose the simplest or most impulsive decisions without analyzing potential consequences.

The Emotional Context of the Game

- A competitive atmosphere increases aggression and competition.

- A cooperative context promotes collaboration by fostering a sense of community.

How Past Experiences Shape Our Game Decisions?

People often use past experiences as a reference point for decision-making. This phenomenon is called the availability heuristic: a player chooses strategies that worked in similar situations before.

- The Impact of Positive Experiences

If a certain strategy previously led to success, a person is likely to repeat it.

Example: If a compromise ensured success in a cooperative game, the player will be more inclined to take this path again. - The Impact of Failures

Negative experiences, on the other hand, can lead to avoiding certain strategies, even if they are potentially beneficial in new conditions.

Example: If in a past game, a player trusted a partner and was deceived, they might avoid cooperation in the future.

Formation of Behavioral Patterns

People tend to form habits in game situations, even if these habits are not always optimal.

Example: A person might always avoid risk, even when it is justified.

The psychological dimension of game theory provides deeper insights into human behavior. Personality traits, emotional states, and past experiences shape strategy choices and often disrupt idealized rationality. Considering these factors not only improves decision-making effectiveness but also helps build long-term, beneficial relationships with other players.

Game Theory in Real Life

Game theory extends far beyond mathematical models and finds its application in many aspects of everyday life. It helps explain why people make certain decisions in social, professional, and personal situations. At some point, each of us becomes a player, choosing strategies that maximize our benefits or minimize risks.

In real life, game theory explains behavior in conflicts or cooperation-oriented situations, influences our financial decisions, and shapes communication dynamics. It provides tools to analyze such scenarios, helping not only to understand our own motives but also to predict the actions of others.

Social Situations: Why Do We Help or Compete?

In social situations, we constantly face a dilemma: cooperate with others or act in our own interests. Game theory explains why people sometimes help, even if it doesn’t bring them direct benefits, or, conversely, compete, risking mutual harm.

Example: The Prisoner’s Dilemma in Everyday Life

Imagine two neighbors considering improving their shared yard. If both contribute to the project, they’ll enjoy a comfortable living environment (cooperation). If one neighbor avoids contributing while the other does all the work, only the first benefits (deception). If both refuse to participate, the yard remains neglected (mutual loss).

Explanation via Game Theory:

- If the neighbors trust each other, they will choose cooperation.

- If there’s mistrust, they may avoid expenses, leading to a shared loss.

This scenario is common in life, from community initiatives to small group interactions. Understanding these processes helps establish trust and form successful cooperation strategies.

Relationships and Communication: Strategic Interaction in Couples or Teams

In personal and professional relationships, we often need to make decisions that depend not only on our desires but also on others’ reactions. In such situations, it’s essential to consider partners’ interests while predicting their actions.

Personal Relationships

- In a couple, each partner chooses strategies that can either strengthen or weaken the relationship.

- Example: During a conflict, should one concede for the sake of harmony (cooperation) or insist on their position (competition)?

Example: A couple discussing budget distribution. If both partners openly share their needs, they reach a mutually beneficial decision. If one partner hides their true plans, the other may feel deceived, breaking trust.

Teamwork

- In teamwork, it’s essential to consider the interests of each participant.

- Cooperation strategies ensure efficiency, while competition can lead to conflicts.

Example: In a project team, everyone chooses whether to work productively or shift responsibilities to others. If all cooperate, the team achieves high results. If someone avoids responsibility, it creates additional workload for others and reduces efficiency.

Game Theory in Financial and Career Decisions

Finance and career are areas where strategic thinking is crucial. Game theory helps analyze competitors’ behavior, predict market trends, and make decisions that maximize benefits.

Financial Decisions

- Investors choose strategies based on expectations of market behavior.

- Example: Buying or selling stocks depends on forecasts about how other market players will act.

Example: Imagine two entrepreneurs selling the same product. If they agree on stable prices (cooperation), both achieve stable profits. If one lowers prices to attract customers, the other incurs losses and is forced to lower prices too (competition).

Career Decisions

- In career growth, a person decides whether to work independently or build connections by helping others.

- Example: In a competitive environment, cooperation with colleagues can lead to mutual success, but the risk of mistrust remains.

Example: An employee may choose to cooperate with colleagues to achieve company goals, expecting this will lead to a promotion. However, competition for a position can sometimes force individual actions, even at the cost of conflicts.

Game theory in real life helps explain behavior in various spheres, from social interactions to financial decisions. It reveals why we cooperate or compete, how trust and conflicts form, and how strategies can be optimized for the best outcomes. Applying the principles of game theory in everyday life promotes more conscious decision-making and the development of effective relationships.

Game Theory and Manipulation

Manipulation is a situation where one party uses psychological or strategic techniques to influence the decisions of another party to its advantage. Game theory, with its focus on analyzing strategies and outcomes, often becomes a tool for such actions. Manipulators may apply it to compel other players to act in ways that are not in their best interest but are beneficial to the manipulator.

Recognizing manipulative strategies is crucial for protecting your interests and making decisions that reflect your true priorities. Game theory also provides tools to develop defensive strategies that help avoid manipulation.

How to Recognize the Use of Game Theory for Manipulation?

Manipulation is based on creating situations where the other party:

- Misjudges their own benefits.

- Acts under pressure or in response to distorted information.

- Makes decisions that are advantageous only to the manipulator.

Typical Signs of Manipulation

- Lack of information transparency: The manipulator may hide important information or present it in a distorted way.

Example: During negotiations, one party conceals that they have an alternative option, forcing the other party to make concessions. - Creating an illusion of choice: The manipulator offers several options, but all are beneficial only to them.

Example: In an advertising campaign, a consumer is offered a “discount” that is actually already included in the product’s price. - Emphasizing risks: The manipulator deliberately focuses on potential losses to evoke fear and push the other party toward a specific decision.

Example: In a conflict, one player threatens “mutual loss” to force the opponent to concede. - Using authority or emotional pressure: The manipulator may appeal to authority, emotions or guilt.

Example: “If you refuse to cooperate, our friendship will suffer.”

Defense Strategies: Staying True to Your Interests

Once manipulation is recognized, the next step is to develop a defensive strategy. It should aim to preserve your interests and prevent exploitation.

Key Principles of Defense

- Careful analysis of the situation:

- Maintain objectivity and avoid hasty decisions.

- Evaluate all possible options and their consequences.

- Ensure you have all the necessary information.

- Maintaining emotional calm:

- Manipulators often use emotions to influence you.

- Take a pause to reduce emotional tension.

- Make a conscious choice without succumbing to pressure.

- Fact-checking:

- Verify the accuracy of the information provided.

- Ask clarifying questions.

- Involve experts or third parties if possible.

Specific Defense Strategies

- Establishing the rules of the game:

- Insist on transparent interactions, e.g., request written agreements.

- Declare your principles: “I am ready to cooperate, but only on mutually beneficial terms.”

- Risk management:

- Use backup plans (alternative options).

- In conflict situations, reserve the right not to accept any of the proposed options if they do not suit you.

- Counter-manipulation:

- Use the “mirror method”: reflect the manipulator’s behavior to force them to reveal their true intentions.

- Offer an unexpected alternative that shifts the manipulator out of their advantageous position.

Example of Defense

During negotiations, a partner tries to force you to make a quick decision so you don’t have time to analyze the situation. Strategy: Politely postpone your response, explaining that you need time to think. Simultaneously, verify all details of the agreement.

Is Winning Always a Victory?

In game theory, the concept of winning is often associated with victory, but winning does not always mean achieving the best result. A victory can be individual but simultaneously harm other participants or even the winner in the long term. In some cases, one party’s success means losses for another, creating a foundation for conflicts and mistrust.

The “Win-Win” Concept in Game Theory

Classic game theory often considers zero-sum scenarios, where one party’s gain equals the other’s loss. However, in real life, many games have non-zero sums, meaning scenarios are possible where both sides win through cooperation.

What is “Win-Win”?

This is a situation where all participants benefit from mutual cooperation or compromise. Such an approach avoids conflicts and builds long-term positive relationships.

Examples of “Win-Win”

- Business: Two companies collaborate on a joint project, reducing costs and increasing profits.

- Personal relationships: Partners agree on the distribution of household responsibilities, ensuring comfort and harmony.

How to Achieve “Win-Win” in Real Life?

- Openness and trust: Discuss the needs and interests of all parties.

- Shared vision of goals: Seek solutions that meet the key interests of both parties.

- Compromises: Be willing to concede on less significant issues.

Ethical Issues: Can Manipulative Strategies Be Justified?

Ethics in game theory is a separate dimension that influences how we perceive winning. Manipulative strategies often benefit one side, but their use raises questions about the morality of such an approach.

When Might Manipulation Seem Justified?

- In critical situations where other options are unavailable (e.g., protection against fraud).

- To achieve the greater good if the ends justify the means.

Ethical Dilemmas of Manipulation

- Risk of losing trust: Manipulative strategies can ruin long-term relationships.

Example: In a team, an employee hides important information to gain an advantage, but this causes conflict. - Consequences for the manipulator: Even a win may result in losses if the manipulator’s reputation suffers.

How to Assess the Ethics of a Strategy?

- Does the strategy consider the interests of other parties?

- Does it align with your values and long-term goals?

- Are you ready for the consequences in case of exposure?

Balancing Personal Gain and Common Interest

In many situations, a conflict arises between personal benefit and the need to maintain harmonious relationships with other participants. Resolving this conflict depends on strategic thinking and the ability to cooperate.

Principles of Balance

- Analyze long-term consequences: Is an immediate gain worth potential future losses?

- Build trust: Cooperation with others usually brings more benefits in the long term.

- Consider the context: In some cases, personal gain may be justified if it does not harm others.

Example: Negotiations Between Partners

- If one partner insists on maximum benefit for themselves, it can create tension.

- If both sides consider each other’s interests, this fosters stable and productive relationships.

Strategies for Achieving Balance

- Interest-based negotiation: Focus on the needs of each side rather than positions.

Example: In salary negotiations, consider not just the amount but also working conditions. - Willingness to compromise: Seek solutions that consider the key interests of all.

- Maintaining transparency: Open dialogue helps avoid conflicts.

Winning is not always a victory if it comes at the expense of others or undermines long-term interests. The “win-win” concept offers a more effective and ethical approach to conflict resolution, but its implementation requires a willingness to cooperate and compromise. By analyzing ethical aspects and balancing personal gain with common interests, we can achieve not only short-term success but also long-term harmony in relationships and endeavors.

Conclusion

Game theory is a unique tool that allows us to deeply understand the motivations, strategies, and behaviors of people in various situations. It demonstrates that life is a constant interaction with others, where every choice affects those around us and simultaneously depends on their actions. Understanding these connections helps not only to analyze our own decisions but also to better grasp why others act the way they do. Game theory makes us ponder: are we always rational? Can our intuitive or emotional decisions be optimal?

In practice, game theory is particularly useful in resolving conflicts, building relationships, and making important decisions. It teaches us to look for solutions that benefit not only ourselves but also others. For instance, in negotiations, one should strive to reach agreements that consider the interests of all parties. In teamwork, game theory helps efficiently allocate resources and coordinate actions while minimizing conflicts. In everyday life, it aids in avoiding impulsive decisions that might have negative consequences in the future.

To apply game theory in life, it is helpful to remember several key principles. First and foremost, analyze situations and consider all possible outcomes, both short-term and long-term. Openness and a willingness to cooperate often yield better results than competition. Additionally, learn to recognize manipulations and develop strategies that allow you to remain true to your interests while taking into account the needs of others.

The prospects of game theory open numerous opportunities for future research. Applying this approach to areas such as artificial intelligence, environmental challenges, global economics, and social change could drastically transform our understanding of effective decision-making. For example, modeling the behavior of large groups of people based on game theory could help better manage resources or predict the outcomes of political reforms.

Game theory not only explains our present but also provides tools for shaping the future. It encourages us to think strategically, seek harmony between individual and collective interests, and make decisions that create sustainable and mutually beneficial outcomes. In a world that is becoming increasingly complex and interconnected, knowledge of game theory can be the key to living successfully in harmony with others.

Examples of Practical Games for Understanding Concepts

Practical games are an excellent way to consolidate knowledge about game theory and learn to apply its concepts in life. They help understand strategies, decision-making, and the consequences of choices in uncertain conditions.

- “Prisoner’s Dilemma”

Rules: Two suspects are detained by the police. They are separated and given the following options: if one confesses while the other remains silent, the confessor gets a reduced sentence, and the silent one gets the maximum sentence. If both confess, they get a medium sentence. If neither confesses, they both get the minimum sentence.

Goal: Understand how cooperation and distrust influence decisions.

Real-life application: In business, the “prisoner’s dilemma” models competition between two companies. - “Splitting the Pie”

Rules: One player proposes how to divide a fixed amount of money between themselves and another player. If the second player agrees, both receive the money. If they disagree, no one receives anything.

Goal: Study the role of fairness and emotions in decision-making.

Real-life application: Modeling negotiations and business deals. - “Hawks and Doves”

Rules: Participants choose either the “hawk” (aggressive) or “dove” (peaceful) strategy. Hawks have the chance to gain more but risk greater losses when encountering other hawks. Doves, while earning less, rarely incur losses.

Goal: Show how strategy depends on expectations of others’ behavior.

Real-life application: Relations between countries or competing companies. - Coordination Game

Rules: Two individuals must make the same choice to win. For example, agreeing on where to meet: at the cinema or a café. If their choices do not match, they gain nothing.

Goal: Learn to coordinate actions and make decisions under uncertainty.

Real-life application: Organizing joint projects at work or within a family. - “Tragedy of the Commons”

Rules: Participants share a common resource (e.g., water or grazing land) that they use for their needs. If everyone acts solely in their own interest, the resource becomes depleted.

Goal: Understand how to balance personal interests with community needs.

Real-life application: Managing natural resources, environmental policy. - Trust Game

Rules: One player decides how much money to transfer to another. The transferred amount is multiplied, but the second player decides how much to return to the first.

Goal: Study the relationship between trust and cooperation.

Real-life application: Building business and personal relationships.

These games not only enhance understanding of game theory concepts but also allow experimentation with different strategies in a safe environment, teaching how to make decisions, analyze others’ behaviors, and find optimal ways of interaction.

Recommended Literature

For a deeper understanding of game theory and its application in real life, it is important to refer to authoritative sources. These will help not only grasp the basic concepts but also explore practical examples and innovative approaches in the field.

- John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern – “Theory of Games and Economic Behavior”

This foundational work initiated the development of modern game theory. The authors detail mathematical models of strategic interaction and explain how they can be applied to economics. - John Nash – “Essays on Game Theory”

While this work is more technical, it is worth reading to understand the concept of Nash equilibrium. This idea became the foundation for many modern studies. - Martin Shubik – “Game Theory in the Social Sciences”

This book examines game theory in the context of social and political relations, demonstrating its significance for conflict resolution. - Ken Binmore – “Game Theory: A Very Short Introduction”

A compact and accessible book that explains the main concepts of game theory without complex mathematical details. - Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein – “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness”

While this book focuses more on behavioral economics, it explains how strategic decisions influence people’s behavior in real life. - Eric Berne – “Games People Play”

Although this is more about the psychology of interactions, the concepts of strategies and scenarios here are linked to the basics of game theory.