The Trolley Problem is one of the most famous moral experiments that explores how people make ethical decisions in a dilemma. Imagine the following scenario: a trolley is moving down the tracks, threatening the lives of five people on its current path. You are standing next to a lever that can redirect the trolley onto another track, where only one person is located. Your choice: do nothing, allowing the trolley to kill five people, or activate the lever, redirecting the trolley and causing the death of one person.

This experiment was proposed by philosopher Philippa Foot in 1967 and later expanded by Judith Jarvis Thomson, who introduced new variations. The primary aim of this dilemma is to make people reflect on how they value life, the morality of their actions, and the limits of responsibility for their choices.

The Trolley Problem extends beyond philosophical musings and holds significant meaning for various disciplines:

- In moral philosophy, it helps analyze the conflict between two fundamental ethical approaches:

- Utilitarianism (maximizing overall well-being): choosing to save five lives at the cost of one.

- Deontology (adherence to moral principles): refusing to kill someone even to save others.

- In psychology, this dilemma examines how people make decisions under pressure. It highlights the role of emotions, cognitive biases, and cultural differences in moral choices.

- In neuroscience, the Trolley Problem has become a tool for studying brain activity. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), researchers investigate how different areas of the brain are activated depending on whether the dilemma is emotional or rational.

- In practical fields (such as medicine or technology), the problem is applied to discussions about autonomous systems, like self-driving cars, which must “decide” whose life to prioritize in emergency situations.

Thus, the Trolley Problem is a critical tool for understanding our values, moral frameworks, and decision-making processes.

At first glance, the Trolley Dilemma seems to test morality: what matters more—the number of lives saved or adherence to ethical principles? However, deeper analysis reveals that this choice might be an illusion.

- Do we truly have freedom of choice? The dilemma places a person in a situation where any decision seems wrong. Perhaps the problem’s framing forces the brain to operate within specific patterns, creating a conflict between logic and emotions.

- Are we considering all the factors? Real life is more complex than an imagined experiment. In the trolley scenario, we often ignore the context: who are the people on the tracks? Are we truly responsible for their lives?

- Does this problem manipulate our consciousness? The trolley forces limited options on us, preventing broader thinking. Is there another solution that we fail to see because of the dilemma’s structure?

These questions invite us to consider whether the Trolley Problem is a genuine test of morality or merely a trap for our thinking, designed to make us search for answers where there might be none.

The Trolley Problem: The Essence of the Dilemma

The trolley problem is one of the most vivid examples of a moral dilemma, forcing us to ponder complex questions of choice, responsibility, and ethical principles. At its core lies a situation where any decision has grave consequences, and no option appears entirely correct.

The trolley problem has become popular due to its universality: it appeals to fundamental human emotions and ethical principles, prompting us to ask ourselves how we would act in such a situation. Thanks to its simple structure, this dilemma has found applications in philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, law, and even technology.

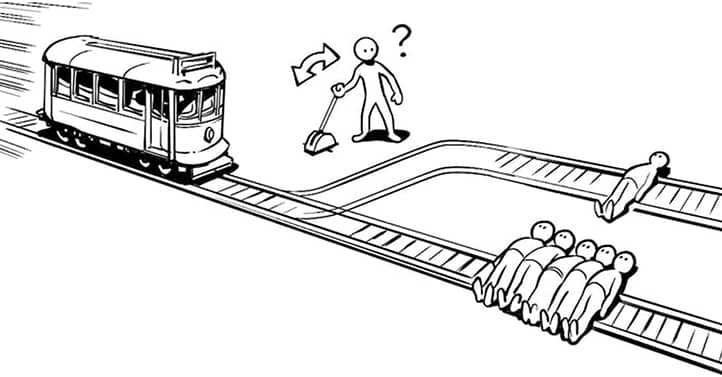

The Classic Trolley Problem

The classic version of the trolley problem, proposed by Philippa Foot, is as follows:

- A trolley is moving along tracks and threatens to hit five people who cannot escape.

- You are standing next to a lever that can divert the trolley onto another track, where only one person is present.

- Your choice: do nothing, allowing the trolley to hit five people, or change its course, causing one person’s death.

This version presents a utilitarian choice: sacrificing one life to save a greater number of people.

Variations of the Dilemma

Over time, the classic dilemma has evolved into numerous variations, complicating the choice and introducing new ethical aspects:

1. The Fat Man Variant

You are standing on a bridge above the tracks with a fat man. The only way to stop the trolley is to push him onto the tracks, saving five people.

- Here, the focus shifts from indirect involvement (switching the lever) to direct action (pushing someone), making the moral choice more challenging.

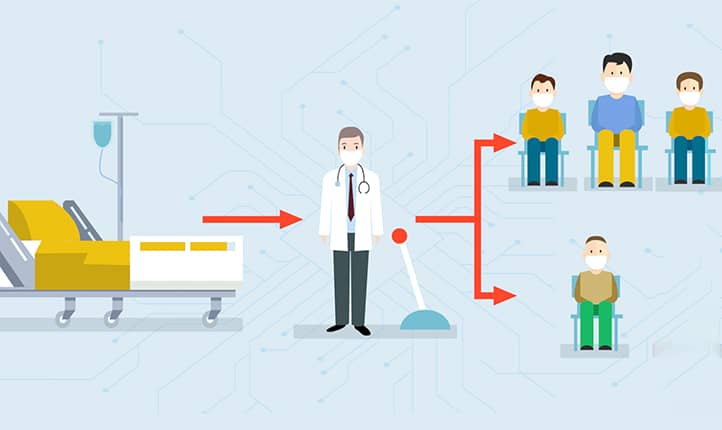

2. The Doctor’s Dilemma

A doctor has five patients in need of organ transplants to survive. There is one healthy patient who could be sacrificed to provide the necessary organs.

- This variation raises questions about the ethical limits of sacrificing one life to save others.

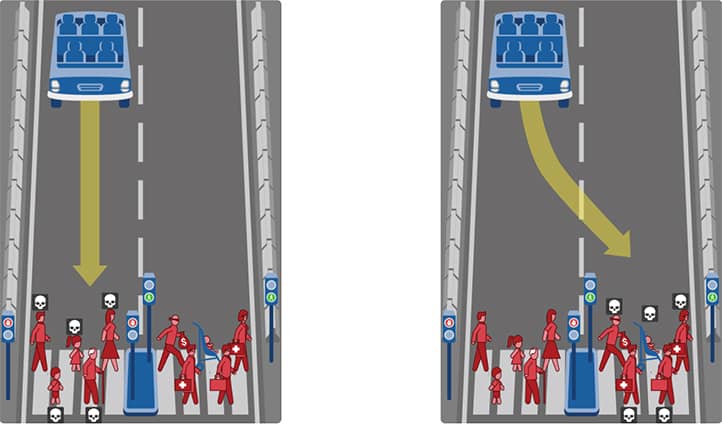

3. Autonomous Vehicles

A self-driving car must decide where to steer during an accident: hit pedestrians or sacrifice passengers inside.

- This modern variation not only addresses moral principles but also challenges the algorithms designed by engineers.

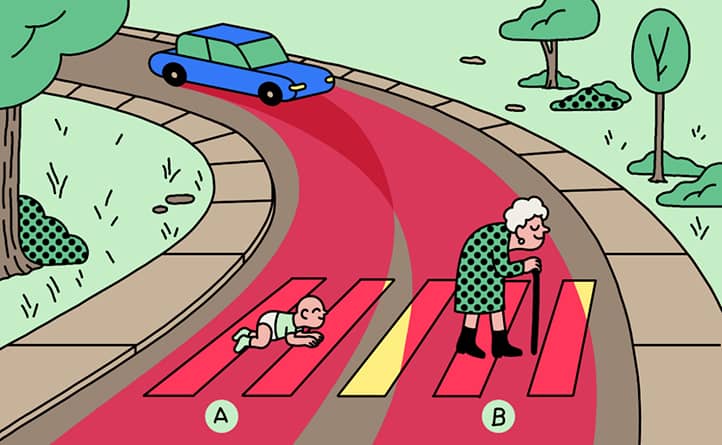

4. Expanded Dilemmas

Some versions add new factors: for example, the five people on the track might be criminals, while the one person is a doctor who saves lives. This forces consideration of not only the number of lives but also their “value” to society.

Common Approaches to Decisions and Their Ethical Implications

- The Utilitarian Approach (switch the lever)

Deciding to divert the trolley to another track, resulting in one person’s death, is based on the principle of maximizing overall well-being.- Positive: More lives are saved, aligning with utilitarian principles.

- Negative: Active involvement in killing one person makes you directly responsible for their death, which could induce guilt.

- The Deontological Approach (do nothing)

Refusing to switch the lever is based on the principle of nonviolence: no one has the right to consciously take another person’s life, even to save more lives.- Positive: You abstain from participating in killing, leaving the outcome to “circumstances.”

- Negative: Allowing more people to die may appear as inaction or indifference.

Most people, when choosing between these options, experience a conflict between emotions and logic. Emotions push us to avoid active involvement (pushing a man or switching the lever), while a rational approach demands evaluating consequences and choosing the “lesser evil.”

In many cases, people’s decisions change depending on how the problem is framed. For example, in the fat man variant, most refuse to push him, despite the same outcomes. This demonstrates the influence of cognitive biases.

The trolley problem illustrates the difficulty of making decisions under conditions of moral uncertainty. It not only forces us to choose between life and death but also reveals profound contradictions in our ethical principles.

Moral Choice

The trolley problem compels us to evaluate how objective and justified our moral decisions can be. In dilemma situations like the trolley problem, we must determine what holds greater significance: the number of lives saved, adherence to moral principles, or our emotions.

Moral choice in such situations reflects a complex interplay between logic, emotions, and sociocultural norms. People from different cultures, social groups, and even personal life experiences approach this question differently, choosing between utilitarianism, deontology, or their own intuitive beliefs.

Utilitarianism: Maximizing Overall Good

Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that asserts the best decision is the one that brings the greatest benefit to the largest number of people. In the context of the trolley problem, utilitarianism suggests that switching the trolley to a track with one person is the right decision, as it saves more lives.

1. Arguments in favor:

- Benefit calculation: The number of lives saved exceeds the number of lives lost.

- Rationality: This decision seems logical from a numerical advantage perspective.

2. Criticism:

- Neglect of individual value: Each life holds unique value that cannot be assessed purely quantitatively.

- Risk of “dehumanization”: The utilitarian approach often disregards emotional and moral aspects of the decision.

Deontology: Adherence to Principles

Deontology, on the other hand, focuses on adhering to moral principles regardless of the consequences. In this case, the deontological approach requires refraining from intervening in the situation, even if it means more people will die.

1. Arguments in favor:

- Avoidance of direct responsibility for killing: Switching the lever or actively intervening is perceived as “breaking” moral boundaries.

- Principle of life inviolability: No one has the right to decide whose death is more “acceptable.”

2. Criticism:

- Passive acceptance of greater loss of life.

- Inability to account for context and practical outcomes.

Thus, the choice between utilitarianism and deontology reveals how our moral attitudes influence our perception of the value of life.

The Impact of Emotions on Moral Decisions

Our emotions play a key role in how we perceive moral dilemmas. Even when attempting to think rationally, emotional reactions often determine our choices.

- Empathy: When a person sees a face or imagines a real individual who might suffer, they are more likely to choose an option that minimizes harm to that individual, even if it contradicts utilitarian principles.

- Guilt: People avoid actions that might make them feel responsible for another person’s death.

- Fear: In critical situations, fear affects the speed and rationality of decision-making.

Emotions often conflict with rational thought. For instance, in the case of the fat man, most people refuse to push someone off a bridge, even if it could save five people, because such an action feels emotionally unacceptable.

However, emotional responses can change depending on the context. For instance, knowing more about the victim or their societal importance can alter the perception of the choice.

Does Choice Depend on Cultural and Social Environment?

Our environment, culture, and social norms also significantly influence how we make decisions in moral dilemmas.

- Western countries: The utilitarian approach emphasizes rationality and quantitative evaluation of life’s value.

- Eastern countries: The deontological approach may prevail due to a greater focus on harmony, collective responsibility, and traditions.

People in responsible professions (e.g., doctors or military personnel) are more likely to make utilitarian decisions because they are accustomed to making difficult choices for the “greater good.”

In more developed countries, individuals may choose decisions based on abstract moral principles, whereas in countries with unstable economies or political systems, choices may be more pragmatic.

Research shows that even the language used to frame the dilemma influences the choice. For example, in many experiments, people were more likely to choose a utilitarian approach when the dilemma was explained using numbers rather than personal stories.

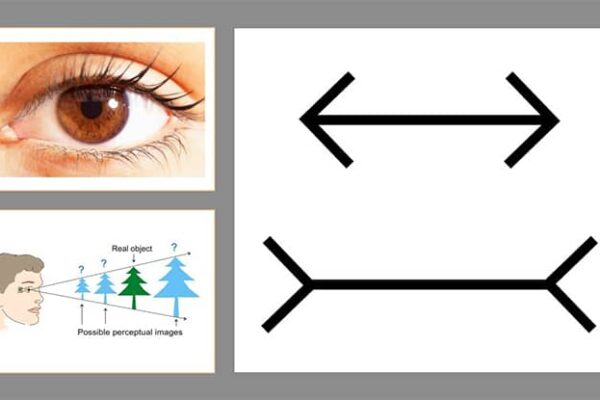

Cognitive Trap

The trolley problem is not just a moral dilemma; it is a test of our thinking. It demonstrates how our brain, faced with complex and contradictory situations, can work “against itself.” In such conditions, cognitive distortions and heuristics often lead us to decisions that seem logical but fail to account for the full complexity of the situation.

This dilemma exploits the brain’s tendency to seek simplicity and efficiency, especially when time or resources for analysis are limited. However, this approach often leads to traps where we choose clear but incorrect answers.

How does the trolley problem make the brain work “against itself”?

The brain has two main systems of thinking:

- System 1: intuitive, fast, emotional.

- System 2: analytical, slow, rational.

In the trolley dilemma, these systems come into conflict:

- System 1 immediately reacts to the moral aspect of the situation: “I can’t kill a person!”

- System 2 analyzes the consequences: “Switching the lever will save more lives.”

However, in many cases, the emotional reaction of System 1 prevails, forcing us to make decisions that contradict a rational approach.

Cognitive Load:

The trolley problem creates conditions under which the brain becomes overloaded:

- One must simultaneously consider the number of victims, moral principles, and personal responsibility.

- As a result, the brain seeks a “quick way out,” often neglecting critical aspects.

The dilemma imposes the illusion that there are only two options: active action or inaction. This forces us to focus on limited scenarios, ignoring possible alternatives.

Heuristics and Cognitive Distortions in Moral Dilemmas

Heuristics are “mental shortcuts” that allow the brain to make quick decisions. In the context of the trolley dilemma, they can act as traps:

- Availability heuristic: A person chooses the option that seems more familiar or simple. For instance, switching the lever appears less active than pushing a person off a bridge, so it seems “more correct.”

- Framing effect: Decisions may depend on how the problem is presented (e.g., emphasis on “saving” five lives or “killing” one person).

Cognitive Distortions

- Identifiable victim effect: People react more emotionally to a specific individual they “kill” than to five abstract people.

- Status quo bias: People tend to do nothing if active actions could lead to loss, even if inaction has worse consequences.

- Anchoring effect: Decisions may depend on initial information or context. For example, if the five people are described as “innocent children,” the choice shifts.

Researchers, such as Professor Joshua Greene, have shown that emotional and cognitive reactions to dilemmas change depending on how the scenario is described. This proves that distortions are not objective reality but depend on context and information presentation.

Why does the brain prefer simple but incorrect answers?

- Striving for efficiency. The brain evolved to make quick decisions under conditions of limited time or information. In complex situations like the trolley problem, this drive for speed becomes a trap because:

- Simple choices seem more understandable and less risky.

- Emotional reactions help avoid the discomfort of prolonged analysis.

- Role of Cognitive Economy

- The brain spends minimal resources on complex reasoning, reducing the ability to analyze long-term consequences.

- Instead of objective evaluation, the brain relies on prior experience or familiar patterns.

- Avoiding Responsibility. Simple answers help avoid guilt or cognitive dissonance:

- For example, the decision to “do nothing” seems less active, so a person feels less “guilty.”

- Switching the trolley seems technical rather than moral, reducing the sense of personal responsibility.

The trolley problem demonstrates how cognitive biases and brain limitations prevent us from making balanced decisions. It shows that our “automatic” reactions, while seemingly correct, are often the result of the brain working “against itself.” This cognitive trap urges us to approach our thinking process more critically, especially in moral matters.

Ethical Experiments in Real Life

The trolley problem might seem like a purely hypothetical experiment designed for philosophical debates. However, its significance extends far beyond abstract moral theory. Modern society faces similar dilemmas in real-life situations that require difficult decisions between life and death, societal benefits, and individual rights.

This dilemma helps better understand how people make moral decisions under critical conditions and influences the development of policies, technologies, and institutions. In medicine, military actions, autonomous vehicle technologies, and even environmental policies, the choice between individual and collective good becomes highly relevant.

Does the Trolley Problem Have Practical Applications?

- Autonomous Vehicles and Moral Algorithms. One of the most striking examples of the trolley problem’s practical application is programming autonomous vehicles. Developers must consider potential emergency situations where the car needs to “choose” whom to save:

- For instance, should preference be given to the pedestrian or the passenger in the car?

- What factors should influence the decision: the number of potential victims, age, or social status?

Studies show that different cultures prioritize differently. For example:

- In Western European countries, greater emphasis is placed on the number of lives saved.

- In Asian countries, age (favoring younger individuals) plays a significant role.

- Resource Allocation in Medicine. The trolley problem is often used to analyze ethical decisions in medicine, such as:

- Who should be treated first in resource-scarce conditions (e.g., during pandemics)?

- How should organs for transplantation be allocated when the number of patients exceeds donors?

In such situations, utilitarian principles (maximizing lives saved) often conflict with the emotional or moral convictions of healthcare workers.

- Environmental Policy. Large-scale environmental decisions (e.g., reducing emissions) confront governments with similar dilemmas: should current economic prosperity be sacrificed for the sake of future generations?

How Do People Make Similar Decisions in Everyday Situations?

- Medicine. Medical professionals frequently encounter ethical dilemmas similar to the trolley problem:

- Triage during disasters: Who should be treated first when resources are limited?

- Turning off life support: Is it ethical to withdraw life support when recovery chances are minimal?

In such cases, doctors rely on both utilitarian approaches (maximizing saved lives) and ethical principles that mitigate feelings of guilt for the decision made.

- Military Actions. In military operations, commanders often face decisions reminiscent of the trolley problem:

- For example, should a small group of soldiers be sacrificed to save a larger group or achieve a strategic goal?

- Striking locations where civilians might be present to eliminate an enemy is another typical moral dilemma.

Such decisions involve emotional pressure and are often re-evaluated from an ethical perspective after the actions are completed.

- Emergency Situations. Rescue workers in natural disasters must choose whom to save when it is impossible to help everyone simultaneously. For example:

- Should children be saved first, or those in the greatest danger?

- How should decisions be made when it’s impossible to help everyone at once?

In such situations, decisions often rely on quick heuristics that simplify moral choices.

Examples of Modern Research Based on the Trolley Problem

- Virtual Simulations and Experiments. Researchers increasingly use virtual technologies to simulate the trolley problem in realistic conditions. For example:

- Participants are asked to control a vehicle in a simulation where they must “choose” whom to save.

- Such studies evaluate how emotions, stress, and time constraints affect decision-making.

- Studies on Cultural Differences. Trolley problem experiments conducted in various countries aim to understand how culture influences moral decisions. For example:

- In Western countries, an emphasis on rationality (utilitarianism) is more common.

- In Eastern countries, traditions and group harmony play a significant role.

- Neuroethics and Brain Studies. Using MRI, researchers examine which brain areas activate when people make decisions in moral dilemmas. Findings reveal:

- Emotional reactions are linked to activity in the limbic system.

- Rational decisions activate the prefrontal cortex.

- Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. Studies explore how people perceive algorithms that make moral decisions. For example:

- Do people trust autopilots in life-and-death situations?

- Should programs consider cultural or personal factors in their decisions?

Thus, the trolley problem transcends philosophical discussions, finding reflection in real-life situations. It helps better understand how people make decisions and serves as a tool for developing fairer policies, technologies, and ethical standards.

Criticism of the Trolley Problem

The trolley problem is one of the most well-known moral experiments, but its popularity is accompanied by numerous discussions and criticisms, with many researchers, philosophers, and practitioners questioning the applicability of the dilemma to real-life situations.

Opponents of the dilemma argue that it oversimplifies the complexity of moral decisions and neglects emotional, social, and cultural factors. They also emphasize that such experiments create overly hypothetical scenarios that rarely occur in reality. Proponents, however, believe that the trolley problem offers valuable insights into how human morality functions and how we make decisions in value conflict situations.

Arguments for the Use of the Trolley Problem

1. Exploring fundamental principles of morality. The trolley problem allows the study of fundamental ethical questions:

- What is more important: the outcome (utilitarianism) or the principles (deontology)?

- How do people evaluate the value of life and responsibility for actions?

It helps reveal how we balance the desire for rationality with emotional convictions.

2. Simplicity and universality. The hypothetical scenario of the dilemma is clear and easily adaptable to various cultural and social contexts. This makes it an effective tool for comparing moral systems across different groups and societies.

3. Applications in real-world domains. The trolley problem has practical significance for analyzing complex decisions in medicine, technology, and politics. It aids in designing more ethical algorithms for autonomous systems or policies for resource distribution.

Arguments Against the Use of the Trolley Problem

1. Hypothetical nature and detachment from reality. The trolley problem is often criticized for creating artificial situations that rarely occur in real life. People seldom face the need to choose between life and death under such simplified conditions.

2. Oversimplification of moral decision-making complexity. In real-life situations, moral decisions are multidimensional:

- They depend on context, relationships with the affected parties, cultural factors, etc.

- The trolley problem ignores these aspects, reducing complex moral dilemmas to a binary choice.

3. Psychological and emotional impact. The dilemma does not account for stress, fear, and emotional aspects that significantly influence real moral decisions.

It may also cause emotional discomfort for participants in such experiments, which can affect the results.

4. Cultural and social bias. The dilemma was created within the framework of Western ethical tradition, and its conclusions may not align with moral systems of other cultures, where decision-making is based on collectivism or religious principles.

Thus, the trolley problem is a valuable tool for analyzing moral principles and cognitive processes, but it has significant limitations. It helps understand basic mechanisms of thought but does not always accurately reflect the complexity of real moral choices. This underscores the need to complement it with other methods and tools to gain a more comprehensive understanding of morality and ethics.

Conclusion

The trolley problem, despite its hypothetical nature, remains a powerful tool for studying moral principles, cognitive mechanisms, and human nature. It prompts us to reflect on how we make decisions in moral dilemmas and whether these decisions are truly a product of our ethics or merely the result of cognitive traps and biases.

This experiment highlights the fundamental tension between the utilitarian approach, which seeks the greatest good for the greatest number, and deontological principles, which emphasize the inviolability of certain moral laws. Ultimately, the trolley problem demonstrates that neither approach can fully satisfy all aspects of morality, as each has its limitations. This forces us to reconsider our views on ethics as something unequivocal and constant.

At the same time, the trolley problem shows how our brains often seek simple solutions even in complex situations. Heuristics and cognitive distortions influencing our thinking can lead us into traps where we consider choices obvious, while in reality, they may be superficial or even flawed. This once again confirms the importance of developing critical thinking and the ability to analyze not only the consequences of our decisions but also the process of making them.

One of the main lessons of the trolley problem is that ethics is not just a set of rules but a mirror of human nature. It reveals how strongly our decisions are influenced by emotions, social context, culture, and even our personal history. It teaches us to be more attentive to our values and ready to acknowledge that our moral judgments are far from always rational or universal.

This dilemma also invites us to reflect on the question: What defines our system of values? Is it the result of rational choice, cultural influence, or intuitive reactions? Answers to these questions can change our understanding of ourselves and how we make decisions in important life situations.

Unfortunately, the trolley problem does not provide definitive answers and does not aim to do so. It invites us to delve deeper into ethics, human thinking, and our relationship with the world. It challenges each of us to think about how our value system affects decision-making and whether we are ready to take responsibility for our choices, even if they are difficult and ambiguous.

Recommended Reading

For a deeper understanding of the trolley problem, moral dilemmas, and cognitive traps, I recommend exploring the following works:

- “The Secret Life of the Mind: How Your Brain Thinks, Feels, and Decides” – Mariano Sigman. This book offers a revolutionary view of the role of neuroscience in our lives, uncovering the mysterious processes in the brain that determine how we learn, think, feel, and dream.

- “Thinking, Fast and Slow” – Daniel Kahneman. In this work, Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman explores two systems of human thinking—slow and fast—and shows how they influence our decisions and judgments.

- “Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions” – Dan Ariely. The author examines why people often make illogical decisions and how understanding these irrational aspects can help avoid cognitive traps.

- “Moral Machines: Teaching Robots Right From Wrong” – Wendell Wallach and Colin Allen. This book explores how moral dilemmas, like the trolley problem, can be accounted for in designing ethical algorithms for artificial intelligence.

- “Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do?” – Michael Sandel. Professor Sandel analyzes various moral dilemmas, including the trolley problem, and discusses their practical significance in the modern world.