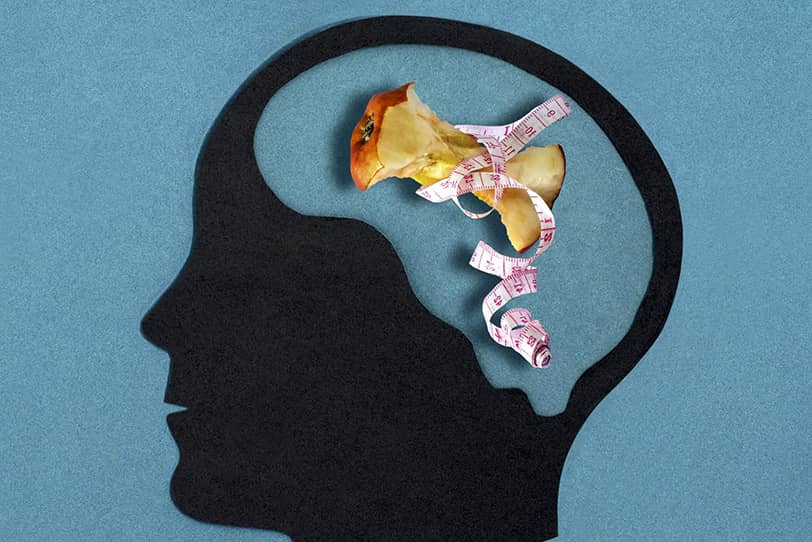

Eating disorders (ED) are not merely “bad habits” or temporary diets but serious mental health conditions in which one’s relationship with food, weight, and their own body becomes obsessive, destructive, and often life-threatening. Anorexia, bulimia, binge eating disorder, orthorexia—all these conditions share one thing: food ceases to be just a way to satisfy hunger, turning instead into a source of agonizing control, fear, or shame.

They are called an “invisible epidemic” for a reason. Unlike other illnesses, EDs are often hidden: sufferers feel ashamed to admit it even to loved ones, mask symptoms, and deny the problem for years. Society still perceives them as a “whim” or a “sign of weak character,” when in reality, they are complex psychophysiological disorders requiring professional help. Social media only worsens the situation: Instagram and TikTok feeds are filled with photoshopped bodies, “perfect” diets, and toxic advice like “how to lose weight in three days.” Under this pressure, teenagers and young adults are especially vulnerable, but adults, including men—who are talked about less—also fall victim to EDs.

The relevance of this topic cannot be overstated. According to the WHO, the number of ED cases has nearly doubled over the past decade, and the mortality rate for anorexia is one of the highest among mental illnesses. The COVID-19 pandemic added fuel to the fire: isolation, stress, and obsessive news about “COVID weight gain” triggered a new wave of disorders. Yet the epidemic remains “silent”—many still don’t know where to turn or fear judgment.

This article is an attempt to break the cycle of silence. How can you recognize warning signs? Why do beauty standards kill? And most importantly—where can you seek help? The answers to these questions could save someone’s life.

What Are Eating Disorders?

Eating disorders (ED) are not just “bad habits” or temporary diets. They are serious mental health conditions in which food, weight, and body shape become obsessive fixations that affect physical and emotional well-being. Unlike ordinary dietary preferences, EDs cannot be controlled by willpower—they alter thinking, behavior, and even the perception of one’s own body.

Many mistakenly believe that these disorders are a “model’s disease” or a “teenage whim.” In reality, they can develop in anyone, regardless of age, gender, or social status. The main danger of EDs is that they often go unnoticed until they cause severe harm to health.

Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia is not simply “refusing to eat.” It is a distorted body image in which a person sees themselves as fat even when their weight is critically low.

Key signs:

- Panic fear of gaining weight, even with obvious underweight.

- Extreme food restrictions (e.g., 500 calories a day or cutting out entire food groups).

- Obsessive calorie counting, weighing oneself multiple times a day.

- Denial of the problem: “I’m just living a healthy lifestyle.”

Consequences:

- Emaciation, muscle loss, hair loss.

- Heart problems, osteoporosis (brittle bones), infertility.

- One of the highest mortality rates among mental disorders.

Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia is characterized by cycles of binge eating followed by “purging” (vomiting, laxatives, excessive exercise).

Key signs:

- Episodes of uncontrollable overeating (can consume thousands of calories at once).

- Attempts to “compensate” for eating—inducing vomiting, fasting the next day.

- Feelings of guilt and shame after episodes.

- Often maintains a normal weight, making diagnosis difficult.

Consequences:

- Tooth enamel erosion (due to stomach acid from vomiting).

- Dehydration, kidney and heart problems.

- Depression, suicidal thoughts.

Binge Eating Disorder

This is not just a “love of food” but uncontrollable episodes of overeating, followed by shame—without attempts to “purge.”

Key signs:

- Consuming enormous amounts of food in a short time (even without hunger).

- Eating in secret, hiding food stashes.

- Self-disgust after an episode.

Consequences:

- Obesity, diabetes, heart disease.

- Social isolation, depression.

Orthorexia (Obsession with “Healthy” Eating)

This is an unhealthy perfectionism around food, where the pursuit of “clean” eating becomes an obsession.

Key signs:

- Fear of “wrong” foods (sugar, gluten, “chemicals”).

- Rigid food rules, anxiety if they are broken.

- Social isolation (avoiding gatherings with “unhealthy” food).

Consequences:

- Nutrient deficiencies (due to cutting out entire food groups).

- Strained relationships with loved ones.

Common Signs of EDs

Regardless of the type of disorder, there are universal “red flags”:

- Constant thoughts about food, weight, calories.

- Rituals (e.g., cutting food into tiny pieces, chewing 50 times).

- Avoiding social situations involving food.

- Sudden mood swings, irritability.

Important to understand: EDs are not a choice but an illness requiring treatment. If you or someone you know notices these signs, seek professional help as soon as possible.

Why Are Eating Disorders an Epidemic?

Eating disorders are often called a “silent epidemic” of our time—and this is no exaggeration. Unlike viral diseases, they are rarely discussed in the news, but their prevalence is growing at an alarming rate, affecting more and more people worldwide. At the same time, most cases remain undiagnosed: many are ashamed of their problem or simply don’t realize they are ill.

What makes EDs a truly widespread issue? First, modern culture is obsessed with appearance and thinness as symbols of success. Second, social media creates an idealized reality where the “perfect body” becomes an obsessive goal. Third, even today, as mental health is discussed more openly, people with EDs often face misunderstanding: “Just start eating normally!”—as if it were a matter of willpower rather than a complex mental disorder.

Statistics: Rising Incidence Over the Last 10–20 Years

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the number of ED cases has doubled over the past two decades, particularly in developed countries.

- Anorexia has the highest mortality rate among all mental disorders: up to 20% of patients die from complications if left untreated.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, ED-related medical visits increased by 30–40% due to stress, isolation, and obsessive health monitoring.

- Every second teenager has tried dangerous diets at least once, while 10–15% develop a full-blown eating disorder.

These numbers are just the tip of the iceberg. Many cases go unreported because people hide symptoms or avoid seeking medical help.

Who Is at Risk?

While EDs can affect anyone, some groups are especially vulnerable:

- Teenagers and young adults (12–25 years old). At this age, the psyche is most sensitive to criticism, and rapid bodily changes trigger anxiety.

- Girls and women. Social pressure on them is stronger: 80% of anorexia and bulimia diagnoses are given to women. But men suffer too—they’re just less likely to seek help.

- Athletes. In weight-dependent sports (gymnastics, figure skating, running) or those emphasizing “lean” muscle mass (bodybuilding), the risk of EDs reaches 45%.

- People in fashion and entertainment. Strict beauty standards force many to resort to starvation or “cleansing.” For example, 40% of models admit they’ve been told to “lose weight for work.”

- Perfectionists and anxious individuals. For them, food becomes a way to exert control in an unstable world.

The Impact of Social Media

Social media is a powerful catalyst for EDs. Here’s how it distorts body image:

- “Before and after” culture. Weight-loss photos create the illusion that thinness = happiness. Meanwhile, no one shows the hunger-induced fainting spells and breakdowns behind the “perfect” shot.

- Fitness gurus and “clean eating.” Many influencers promote extreme diets under the guise of “healthy living,” leading followers to develop orthorexia out of fear of “harmful” foods.

- Photoshop and filters. Even ordinary users edit their photos, setting unrealistic standards. Research shows that teens who spend more than 3 hours a day on social media have a 60% higher risk of developing EDs.

- Toxic communities that teach how to hide EDs: masking symptoms, deceiving family, and avoiding help.

Stigma: Why Do Many Hide Their Struggle?

Despite the prevalence of EDs, thousands go years without help due to fear of judgment. Key reasons include:

- “It’s not an illness, just weakness.” Many still believe that people with EDs “just need to get a grip.” In reality, it’s as much a disease as depression or anxiety.

- Shame and denial. Sufferers often think: “I’m not losing weight fast enough to have anorexia” or “I don’t vomit, so it’s not bulimia.”

- Fear of weight gain. To someone with an ED, the suggestion to “just eat” sounds as terrifying as being told to jump off a roof.

- Medical misunderstandings. Even doctors sometimes say: “Your weight is normal—how could you have anorexia?”—though EDs can occur at any BMI.

EDs are a genuine epidemic—but a “silent” one because society still doesn’t take them seriously. Without shifting attitudes and improving access to care, the situation will only worsen. If you notice signs of an ED in yourself or a loved one, there’s no shame in it. It’s a reason to seek professional help.

Causes of Eating Disorders

Eating disorders never appear “out of nowhere”—they always stem from a complex interplay of multiple factors. When we see someone with anorexia or bulimia, it’s important to understand: behind their relationship with food lie deep psychological wounds, societal pressures, and sometimes biological predispositions. This is not a whim or a sign of weak character, but a serious illness whose roots often stretch far into the past.

At the same time, there is no single guaranteed cause that leads to an eating disorder (ED). For one person, the disorder might develop after a traumatic event; for another, it could be due to prolonged exposure to a toxic environment; while a third might have a genetic predisposition. Most often, the illness is triggered by a combination of several factors. Let’s examine them in detail.

Psychological Factors

The psychological profile of someone with an ED often includes three key traits:

Perfectionism—not just a desire to do things well, but a tormenting need to meet unrealistic standards. For a perfectionist, food becomes:

- A way to exert control in an unstable world.

- An area where they can achieve “perfection” (e.g., an “ideal weight”).

- An obsession: “If I can control my body, then I’m worth something.”

Anxiety manifests in:

- Constant worry about the future.

- Fear of losing control.

- Obsessive thoughts about food and weight.

Many ED patients describe how food restrictions initially bring relief—this is how their psyche finds an outlet for anxiety.

Low self-esteem:

- Often forms in childhood (parental criticism, school bullying).

- Leads to the belief “I’m not good enough.”

- Drives the search for self-worth through weight control.

- Creates a distorted body image (even at a normal weight, the person sees themselves as “fat”).

Important: These traits are not a death sentence! But they create fertile ground for EDs, especially when combined with other factors.

Societal Pressure

Our society is literally obsessed with appearance, and this pressure starts in childhood:

Beauty ideals:

- Media and social media promote a single body type (often unattainable without Photoshop).

- The “cult of thinness” particularly affects girls: studies show that 70% of girls aged 10–13 are already dissatisfied with their bodies.

- In recent years, a new standard has emerged—”toned” thinness—leading to a rise in orthorexia.

Weight-related bullying:

- 63% of overweight children face bullying.

- Even a single hurtful remark (“You’re fat!”) can trigger a lifelong struggle with body image.

- Adults also experience discrimination—at work, in relationships.

Family influences:

- Parents constantly dieting.

- Criticism of a child’s appearance (“Don’t eat so much, you’ll get fat.”).

- Obsession with “clean eating,” dividing food into “good” and “bad.”*

Biological and Genetic Factors

Scientific research confirms that EDs are not just psychological:

Genetics:

- If one parent had an ED, the child’s risk increases by 50–80%.

- Specific genes linked to anorexia susceptibility have been identified.

- However, genes are not a sentence—just one risk factor.

Brain differences:

- People with EDs often have imbalances in serotonin and dopamine production.

- Altered function in brain regions responsible for self-control and body perception.

- Prolonged starvation worsens these changes.

Hormonal factors:

- Hormonal shifts (adolescence, pregnancy) are high-risk periods.

- Thyroid dysfunction can affect eating behavior.

Trauma and Stress

Psychological trauma is one of the most common triggers for EDs:

Abuse (physical, sexual, emotional): Up to 50% of bulimia patients have experienced some form of abuse. Food restriction can be an attempt to:

- “Make myself invisible” (especially after sexual abuse).

- “Punish myself” (“I don’t deserve food.”).

- Regain control over something in life.

Loss of a loved one:

- EDs often develop after severe grief.

- This may be a conscious attempt to “disappear” after the deceased.

- Or an unconscious coping mechanism for pain.

Extreme dieting:

35% of “normal” diets escalate into EDs. Particularly dangerous:

- Very low-calorie diets.

- Cutting out entire food groups.

- “Cleansing” practices.

The body perceives restrictions as starvation, activating survival mechanisms that alter eating behavior at a deep level.

Important: None of these causes are the person’s “fault.” An ED is an illness, not a choice. And like any illness, it requires professional treatment—not judgment.

Health Consequences of Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are not just “complicated relationships with food.” They are severe illnesses that damage the body both physically and mentally. Many underestimate their danger, believing the consequences are limited to weight changes. However, the reality is far worse: EDs attack every system in the body, and some damage remains for life—even after recovery.

These disorders are especially insidious because their consequences develop gradually. At first, a person may feel fine despite extreme restrictions or binge episodes. But with each month, the illness drains the body’s resources, leading to irreversible changes.

Physical Consequences

Cardiovascular damage:

- Bradycardia (dangerously low heart rate, 30–40 beats per minute).

- Arrhythmias that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest.

- Mitral valve prolapse.

- Critically low blood pressure.

- Reduced heart size (“small heart syndrome” in anorexia).

Gastrointestinal problems:

- Chronic constipation and intestinal atony.

- Gastritis and stomach ulcers (especially in bulimia).

- Pancreatitis.

- Esophageal or stomach rupture from overeating.

- Slowed digestion (the body adapts to starvation mode).

Hormonal disruptions:

- Amenorrhea (loss of menstruation).

- Infertility and early menopause.

- Thyroid dysfunction.

- Osteoporosis (brittle bones) due to estrogen and calcium deficiency.

- Impaired cortisol (stress hormone) production.

Other physical effects:

- Hair loss, brittle nails.

- Dry skin, growth of fine body hair (lanugo).

- Tooth enamel erosion in bulimia (from stomach acid).

- Kidney failure.

- Anemia and weakness.

- Constant feeling of cold (the body conserves energy).

Fatal outcomes:

- Anorexia has the highest mortality rate among mental disorders.

- Main causes of death: cardiac arrest, suicide, multi-organ failure.

- 1 in 5 anorexia-related deaths results from suicide.

Psychological Consequences

Depression and anxiety disorders:

- Persistent guilt and shame.

- Panic attacks triggered by food and weight.

- Loss of interest in life.

- Obsessive thoughts about food and weight (consuming up to 90% of mental energy).

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors:

- 30–50% of ED patients have considered suicide at least once.

- Suicide risk is highest when anorexia co-occurs with depression.

- Feelings of hopelessness (“I’ll never recover”).

Cognitive impairments:

- Memory and concentration problems.

- Slowed thinking (the brain lacks nutrients).

- Difficulty making decisions.

Social isolation:

- Broken relationships with friends and family.

- Job loss or academic decline.

- Avoiding social situations involving food.

- Loneliness and feeling misunderstood.

Important: Many of these consequences are reversible with timely treatment. But the longer the disorder persists, the harder recovery becomes. Some changes—like bone density loss or tooth damage—may be permanent. That’s why seeking help at the first signs of an ED is crucial—it can save not just health, but lives.

How to Recognize an Eating Disorder in Yourself or Loved Ones?

Eating disorders often develop unnoticed, disguised as “healthy lifestyles” or “personality quirks.” A person may deny the problem for a long time, while others might miss warning signs until the condition becomes critical. That’s why it’s crucial to recognize the early signs of EDs—they can help identify the problem in time and seek help.

Important to understand: EDs don’t always involve obvious weight loss or gain. Many people with bulimia maintain a normal weight, while those with orthorexia may appear perfectly healthy. The illness primarily manifests through changes in behavior, thoughts, and self-perception. Let’s examine specific red flags.

Warning Signs

Behavioral Changes:

- Constant talk about diets, calories, “good” and “bad” foods.

- Disappearing to the bathroom immediately after meals (possible vomiting attempts).

- Avoiding shared meals with excuses (“I already ate,” “I’m not hungry”).

- Odd food rituals (cutting food into tiny pieces, rearranging food on the plate).

- Hoarding or hiding food (in binge eating disorder).

- Excessive exercise (especially after eating).

Physical Changes:

- Sudden weight fluctuations (both loss and gain).

- Dental problems (enamel erosion, sensitivity—especially in bulimia).

- Hair loss, brittle nails.

- Constant paleness, dark circles under the eyes.

- Frequent illnesses (weakened immunity).

Emotional Changes:

- Irritability, especially around mealtimes.

- Depressed mood, apathy.

- Extreme self-criticism, particularly about appearance.

- Social withdrawal, avoiding friends.

- Denial (“I’m just eating healthy,” “I have it under control”).

Cognitive Signs:

- Obsessive thoughts about food, weight, and body shape.

- Distorted body image (“I’m fat,” even when underweight).

- Difficulty concentrating.

- Loss of interest in former hobbies.

What to Do If You Notice Symptoms?

If you recognize signs in yourself:

- Try not to panic or blame yourself.

- Keep a food and mood journal (helps assess the severity).

- Ask yourself honestly: “Is my eating behavior preventing me from living a full life?”

- Consult a specialist (psychotherapist, psychiatrist)—it’s not shameful but sensible.

If you’re worried about a loved one:

- Choose the right moment (when both are calm).

- Express concern (“I’m worried about you”), not criticism.

- Avoid accusations and ultimatums (“You’re killing yourself!”).

- Suggest seeing a specialist together.

- Be prepared for denial—it’s part of the illness.

What NOT to do:

- Force-feed or restrict food.

- Monitor every meal.

- Joke about appearance or eating habits.

- Ignore the problem, hoping it will “go away.”

Where to Seek Help:

- Psychotherapist or psychiatrist specializing in EDs.

- Clinics treating eating disorders.

- Support groups (in-person and online).

- Crisis centers (if suicidal thoughts occur).

Remember: The earlier treatment begins, the better the chances of full recovery. EDs aren’t just “bad habits” but serious illnesses requiring professional help. With the right approach, they can be overcome. The key is acknowledging the problem and taking the first step toward solving it.

Treatment and Support for Eating Disorders

Eating disorders require a comprehensive professional approach. Many mistakenly believe that EDs can be overcome alone by “just starting to eat normally.” However, this is a dangerous misconception. Without proper treatment, these disorders often become chronic, causing irreversible damage to physical and mental health. The good news: modern treatment methods show high effectiveness—up to 80% of patients fully recover when seeking timely help.

Treating EDs is like assembling a complex puzzle—it requires simultaneously addressing physiological consequences, psychological causes, and social factors. This isn’t a quick process, but each step toward recovery makes life more fulfilling. Let’s examine why self-treatment is dangerous, which specialists to consult, and which therapy methods have proven effective.

Why Self-Treatment Is Dangerous

Physical Risks:

- Sudden dietary changes after prolonged starvation can cause refeeding syndrome

- Independent attempts to stop purging (vomiting) often lead to severe edema

- Without medical supervision, it’s difficult to properly assess the body’s exhaustion level

Psychological Traps:

- EDs distort thinking—patients can’t objectively evaluate their condition

- Attempts to “get a grip” typically end in relapses that intensify guilt

- Without professional help, underlying disorder causes remain unidentified

Pendulum Effect:

- Strict restrictions often alternate with binge episodes

- A “diet-relapse” cycle develops, worsening the problem

- May transition to a different ED type (e.g., anorexia turning into bulimia)

Who to Consult?

Psychiatrist:

- Assesses condition severity

- Prescribes medication when needed

- Helps with comorbid depression/anxiety

Psychotherapist:

- Addresses psychological ED causes

- Uses various therapies (CBT, schema therapy etc.)

- Develops healthy attitudes toward food/body

Nutritionist:

- Creates personalized meal plans

- Helps normalize metabolism

- Teaches hunger/fullness cues recognition

Other Specialists:

- Endocrinologist (for hormonal issues)

- Cardiologist (for heart problems)

- Dentist (for enamel damage)

Treatment Methods

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT):

- Changes distorted food/weight thoughts

- Teaches trigger recognition/coping

- Includes food journaling

- 60-80% effectiveness for anorexia/bulimia

Family Therapy:

- Crucial for adolescents

- Improves family communication patterns

- Teaches proper support methods

- May include supervised family meals

Medication Support:

- Antidepressants (for depression/OCD)

- Anti-anxiety medications

- GI system normalizers

- Vitamin supplements

Support Groups:

- Provide community/understanding

- Reduce isolation

- Allow recovery experience sharing

- Available in-person and online

Key Treatment Principles

Personalized Approach:

- No universal treatment plan

- Programs consider ED type, stage, and individual factors

Gradual Progress:

- Recovery takes months, sometimes years

- Small victories matter

Comprehensive Care:

- Simultaneous body/mind treatment

- Combined therapy methods

Aftercare Support:

- Relapse prevention

- Periodic check-ins

- Maintaining therapeutic group connections

Remember: Seeking professional help isn’t weakness—it’s self-care. Modern medicine has effective ED treatment tools, and thousands have already walked this path to freedom from food-related obsessions. The most important step is the first one.

Prevention: How to Reduce Risks?

In a world where eating disorders have become a true epidemic, prevention takes on special significance. It’s important to understand: EDs don’t appear suddenly—they are always preceded by a period of developing unhealthy attitudes toward food and one’s body. And it’s at this stage that preventive measures can be decisive. This is especially true for children and adolescents, whose psyches are most susceptible to external influences.

Preventing EDs isn’t just about warning against the dangers of diets. It’s about cultivating a holistic, kind relationship with oneself, developing critical thinking, and creating a supportive environment where a person feels valued regardless of appearance. Let’s explore specific steps that can help prevent the development of eating disorders.

Developing a Healthy Attitude Toward Body and Food

Rejecting diet mentality:

- Learn to view food as a source of energy, not as an “enemy.”

- Avoid labeling foods as “good” or “bad.”

- Practice intuitive eating—eat when hungry, stop when full.

Body neutrality:

- Focus on what your body can do, not how it looks.

- Practice gratitude for your body’s functions.

- Avoid daily weigh-ins.

Self-esteem work:

- Build confidence unrelated to appearance.

- Identify and acknowledge your strengths.

- Practice self-compassion.

Critical Engagement with Social Media and Media

Digital hygiene:

- Unfollow accounts promoting “perfect” bodies.

- Follow body-positive blogs.

- Remember: most social media photos are edited.

Media literacy:

- Analyze advertising—how it creates artificial needs.

- Discuss photo editing and realistic beauty standards with children.

- Seek out media that celebrates body diversity.

Balancing online and offline life:

- Limit social media time.

- Develop hobbies unrelated to appearance.

- Practice “digital detox” days.

The Importance of Open Conversations About Mental Health

Creating a safe space:

- Talk about feelings and emotions in the family.

- Don’t dismiss concerns (“It’s nothing”).

- Show that seeking help is normal.

Education:

- Learn and discuss EDs.

- Debunk myths (“It’s a choice”).

- Talk about the importance of mental health.

Early intervention:

- Notice behavioral changes.

- Express concern gently.

- Offer help without pressure.

Support, Not Judgment: How to Help a Loved One with an ED

Healthy communication:

- Avoid comments about appearance or weight.

- Speak about your feelings (“I’m worried”), not criticism.

- Emphasize that your love isn’t conditional on looks.

Practical help:

- Offer to find a specialist together.

- Accompany to appointments if needed.

- Help establish regular eating patterns.

Emotional support:

- Be patient—recovery takes time.

- Celebrate small victories.

- Remind them you’re there no matter what.

Self-care for supporters:

- Don’t neglect your own needs.

- Seek support for yourself.

- Set healthy boundaries.

Conclusion

Eating disorders are not just a phase or a sign of weak willpower—they are serious mental illnesses that destroy a person’s body and soul. Yet despite their dangers, it’s crucial to remember: EDs are treatable, and thousands worldwide have proven recovery is possible. The key is recognizing warning signs early and seeking professional help—not hoping the problem will disappear on its own. Each day of delay risks irreversible health consequences, while timely intervention offers a real chance for full recovery.

Today, more than ever, we must speak openly and without shame about eating disorders. Silence and stigma only worsen the situation, leaving sufferers feeling alone in their struggle. Everyone can contribute to change—whether by examining their own eating habits, supporting a loved one with an ED, or simply sharing accurate information. Above all, kindness matters—to others and to ourselves. In a world that constantly judges appearance, accepting ourselves and others unconditionally becomes an act of courage.

The path to recovery is rarely simple or linear, but every step is worth it. If you or someone you know is struggling with an ED, remember: asking for help isn’t shameful, and seeing a specialist isn’t weakness—it’s self-care. Modern medicine offers effective treatments, and therapy helps not only normalize eating patterns but also cultivate a healthier outlook on life. Stay attentive to yourself and others, and don’t ignore warning signs—your support might be what helps someone take their first step toward freedom from food-related obsessions. After all, everyone deserves a healthy relationship with food and their body—free from fear, shame, and intrusive thoughts.